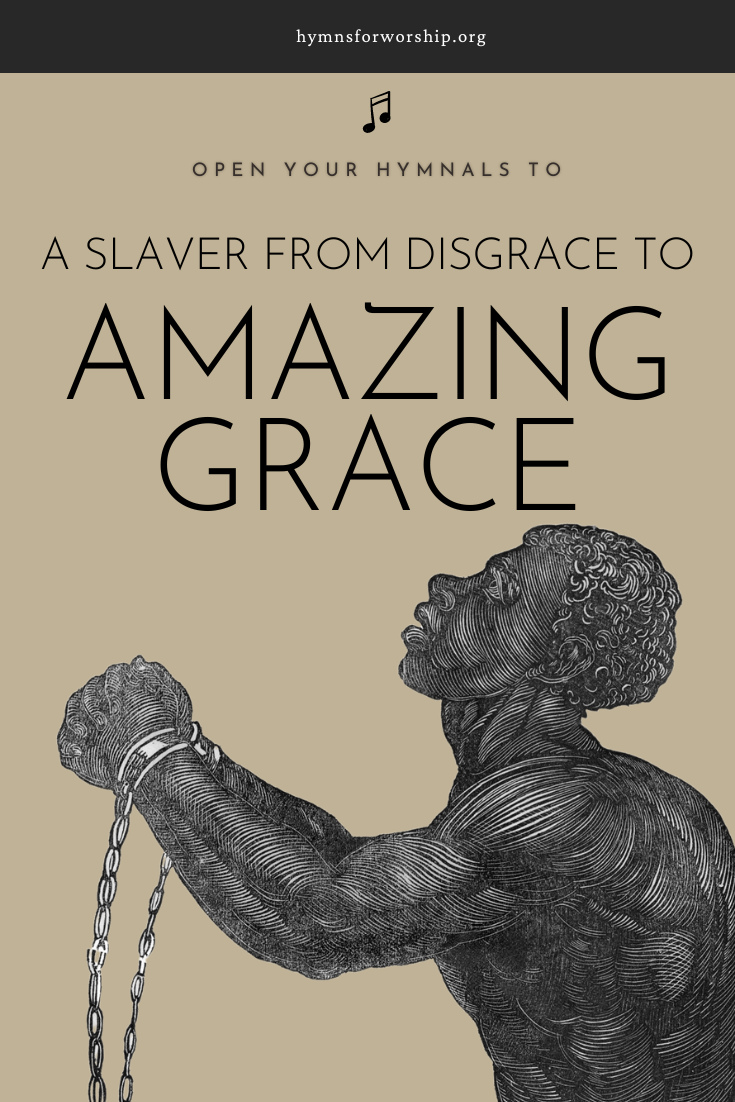

Amazing Grace has gone on to become one of the most powerful songs in the world and a favorite hymn for many because it offers up a universal message of hope and redemption. Some people argue that part of the huge appeal of the hymn is the incredible backstory that brought it to life. John Newton went from being a cruel slave trader to a highly respected minister. Yet although many people don’t know the song’s backstory, the appeal is really in the message because it can be applied to anyone’s life.

This hymn represents the personal journey many people can relate to — wanting to find meaning in our lives through faith. It offers hope to those who are wishing to become better and positively change their life around, yet is does not appear judgmental.

It opens with the powerful lyrics “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me.” Newton drew on his own life working in the slave trade and his near-death experience on a boat, where he believed God saved him and prompted him onto a Christian path. “I once was lost, but now am found; Was blind but know I see”

Early Life of John Newton

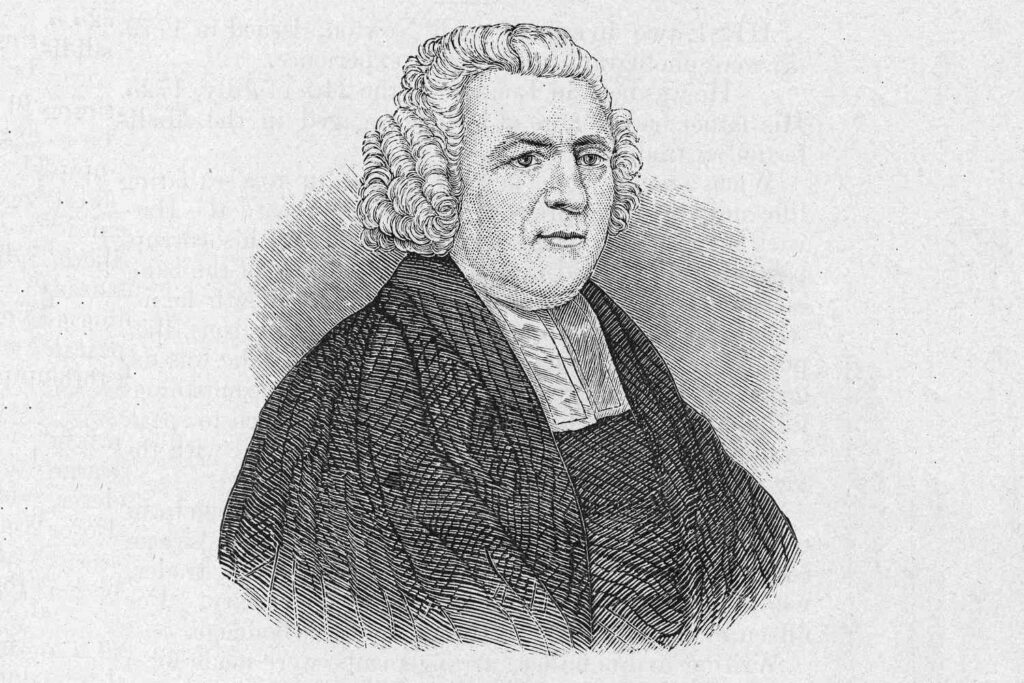

John Newton Jr. was born on July 24th, 1725. Despite an emotionally distant father who was often away due to his job as a Ship’s Captain, John Jr. had a loving mother, Elizabeth. She was a devout Christian who saw her son as a future minister and spent long hours teaching him each day. John was a quick learner and had an exceptional memory, impressing his mother with his thirst for knowledge. Sadly, Elizabeth died of consumption when John was only seven years old, leaving him to run the streets.

John’s father remarried and started a new family, leaving John feeling excluded and on the path to becoming a behavior problem. To discipline him, his father sent him to boarding school, where he was frequently whipped by the brutal headmaster. However, John found salvation in an instructor who recognized his aptitude for Latin, which became a valuable skill later in life.

Time in the British Navy

While on his way to visit friends in 1743, John was captured and forced into the British Navy services. He became a midshipman, an officer of the junior-most rank aboard HMS Harwich. After a failed attempt to escape, he was punished, receiving eight dozen lashes and reduced to the rank of a common seaman.

He was later transferred to another ship, ‘Pegasus’, a slave ship that was heading to West Africa. He didn’t get along with his new crew, and they left him in West Africa in 1745 with Amos Clowe. Clowe was a known slave trader and gave Newton to his mistress, Princess Peye, who treated him terribly. He was starved, tortured and otherwise brutalized just as a slave in the hold of a slave ship.

When Clowe returned Newton approached him and told of his horrible treatment. It did no good, Clowe believed his mistress and after being told that John was stealing from him continued the brutal treatment, and in fact increased it. The only thing that saved John Newton was another slaver nearby who asked that John be released to him. Why Clowe accepted the offer cannot be known. Perhaps he and the princess had satisfied their sadistic yearnings or perhaps they found a new slave to torture. At any rate, though still a slave, John’s treatment improved and though still a slave became like an employee who even made money off his fellow slaves. In a way this was the most dangerous time for John Newton.

Involvement in Slave Trade and Religious Awakening

When John Newton was mistreated by Princess Peye, he managed to smuggle out two letters to his father, who then contacted Liverpool merchant Joseph Manesty to help search for his son. In February 1747, while cruising off the coast of Africa, the ship Greyhound, commanded by Captain Swanwick, spotted a smoke signal followed by a man in a canoe. Swanwick asked the man if he knew anyone named John Newton, to which he replied that Newton was his partner. Without hesitation, Swanwick approached Newton, who seemed to be indifferent about going home, and convinced him to return to England with the mention of an inheritance of four hundred pounds per year and a luxurious trip back home. This was all it took for the woman Newton loved, Mary Catlett, to come to his mind and motivate him to return home and ask for her hand in marriage. It was not money, his father, or anyone else who brought Newton back to reality – it was the woman he loved. Soon, Newton was on a ship watching Africa disappear, eager to start a new chapter of his life with Mary by his side.

During the lengthy trip home, Newton began to read The Imitation Of Christ, perhaps because it was one of the few books on board. As he read, he began to be bothered by the thought: “What if these things be true?” He quickly shut the book. Later that night, on March 9, 1748, he was awakened by many voices. The loudest cried out that the ship was sinking.

On April 8, 1748, John Newton experienced a profound conversion to Christianity. After the Greyhound, endured a harrowing experience, he connected with the God of his beloved mother and recognized His reality. Newton spoke of God with love and respect, rather than disdain. Even he was surprised by his own plea, “If this will not do may the Lord have mercy on us,” after an attempt to shore up the battered ship. Previously, he had sneered at any mention of God, but not anymore. Newton’s references to Jesus Christ were not just foxhole talk. They truly reflected his newfound faith.

Regardless of whether he was a true Christian or not, it did not interfere with his career of buying and selling human beings. It was a distasteful business that required dealing with unsavory individuals. Newton consistently engaged in daily Bible reading and prayer, furthering his self-education by reading Christian and non-Christian texts. He even held services for his crew, despite the fact that some were unruly, similar to their captain’s past behavior. To his credit, he began treating his human cargo with more compassion, as he had developed a conscience. Although practicing the Christian religion can sometimes be a challenge, he took on this burden with determination.

It is not clear if Newton would have ever left the slave trade of his own accord, but he did eventually depart from it due to his failing health in 1754. After experiencing seizures, his physician advised him to pursue a different career. Newton knew he wanted to serve God, and believed that becoming an Anglican priest in the Church of England was the best way to do so. Despite taking over seven years to be accepted, Newton was officially announced as a priest on June 17, 1764. Throughout his time in this role, he gained immense respect from both Anglicans and non-conformists.

Newton now had the opportunity to fellowship with fellow Christians and was no longer involved in the slave trade. This allowed him to fully comprehend the horror of slavery, though it was somewhat ironic that some of his fellow Christians still kept slaves (such as George Whitfield, whose preaching had a great impact on Newton’s faith).

Not only did Newton read the Bible for three hours per day, but he also dedicated time to reading and writing. Already proficient in Latin, he taught himself Hebrew and New Testament Greek. He even wrote a pamphlet in 1756 titled “Thoughts On Religious Associations,” which he distributed to every minister in Liverpool. Newton was now a devout Christian, living and breathing the Gospel, and he longed to preach. He knew that in order to be ordained into the Church of England, he needed to have a thorough knowledge of Greek and Hebrew, which he diligently pursued.

The Power Duo of Olney

Newton’s ordination in the Church of England took seven difficult years, but he eventually became a pastor in the small and poor community of Olney. Despite not being renowned for his preaching, he gained the love of the people by showing them his love. Newton’s fame, however, came from his brilliant and timeless writing. His book, An Authentic Narrative, was an immediate best-seller in 1764 and ran into five additions. It was highly acclaimed by many, including England’s Poet Laureate, William Wordsworth. Although his Review of Ecclesiastical History was never finished, it remains recognized as an important work.

But, of course, Newton was also known for his hymns that have also stood the test of time. He and his friend, William Cowper, collaborated on three hundred and forty eight hymns, with Newton getting credit for 281 and Cowper 67.

Their first volume of Hymns was published as the ‘Olney Hymns’ in 1779. The hymns were written for Newton to use in his Parish. The volume included some of Newton’s most loved hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken” and “Faith’s Review and Expectations” the latter of which many people now know as Amazing Grace. The first line of the song would eventually become the title.

By 1836 the ‘Olney Hymns’ had become very popular and had 37 different recording editions. Newton’s preaching also became admired and his small church was soon overflowing with people who wanted to listen to him.

From Slave Trader to Abolitionist

Like most pastors, no matter their fame, Newton wore out his welcome at Olney. He preached his final sermon there on January 13, 1780, and accepted a pastorate in London. God was working because that’s where he met William Wilberforce. The ex-slave ship captain was about to help in putting an end to slavery.

Beginning in 1785, John Newton began to speak out on the slave trade and became mentor to William Wilberforce, member of Parliament, who was leading the fight to abolish the slave trade. In January 1788, Newton published Thoughts Upon The African Slave Trade. “I hope it will always be a subject of humiliating reflection that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

On December 15, 1790, his heart shuddered once more when his beloved wife, Polly, died of breast cancer. In the years that followed, Newton began to lose his memory. Although his thoughts were limited, Newton said he could remember two things, “That I am a great sinner, and that Christ is a great Savior.” What a conviction of a newly found life that he found only in Christ

John Newton preached his last sermon in October of 1806, and joined Polly in death on December 21, 1807. Newton did live long enough to see the signing of The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Learn the hymn

Printables, piano accompaniment, hymn text and other tidbits are all available in this site.

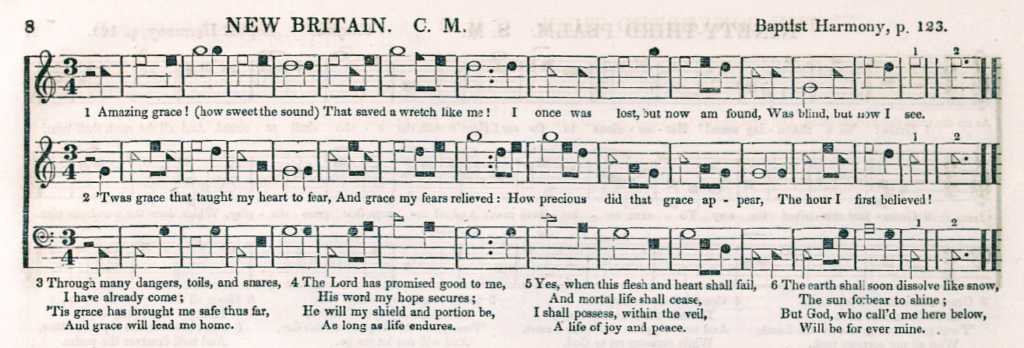

New Britain

Surprisingly, there was never any music written for the song. Newton’s lyrics were attached to several different traditional tunes. The hymn was even forgotten in England, but in the USA it was treasured in the Appalachian valleys and partnered with the American folk melody now known as NEW BRITAIN or AMAZING GRACE.

This was published in Columbian Harmony, or Pilgrim’s Musical Companion (Cincinnati, 1829) and in Virginia Harmony (Winchester, Virginia, 1831). Eventually, it was paired with Newton’s words for the first time by William Walker in Southern Harmony (1835) and included in shape-note hymnbooks thereafter. Walker called the tune NEW BRITAIN. It was modified to its ‘upright’ form and called AMAZING GRACE by Edwin O. Excell in Make His Praise Glorious (Chicago, 1900) and re-arranged in his Coronation Hymns (1910).

The combination of words and tune must have contributed to the hymn’s remarkable revival in the 1960s, when it was taken up by a pipe band and by various popular singers, sometimes in secular contexts. ‘Amazing grace’ now appears in many major British, American, Canadian and Australian hymnals.