In the early 18th century, a trend burgeoned along the lines of American music and music education. When the early settlers fled to the New World for religious freedom, they also brought along with them the practice of singing hymns and psalms in their worship services. Unfortunately, as a distinct body of folk American music grew and newer psalm tunes were composed and the worship liturgy becoming more organized, it became challenging for the congregation to learn new music.

‘Lining-out’ is a form of a cappella hymn-singing or hymnody in which a leader, often called the clerk or precentor, gives each line of a hymn tune as it is to be sung, usually in a chanted form giving or suggesting the tune. Since most parishioners, in the 18th and early 19th centuries could not read words, much less music, this provided a way to sing many hymns without having memorized the words, as the congregation could follow the leader.

However, this soon proved to be catatrophic because not everyone in the congregation can echo the tunes in an accurate manner. Often times, the whole experience proved to be a cacophony that made the worship service sound irreverent and shoddy.

As a remedy to the ‘lining-out’ disasters in many churches, singing schools were established. Congregants were taught to read notes, sing properly, and learn a basic repertoire of sacred and choice secular songs.

A singing master is usually hired to teach children, young people and interested adults. The school usually last a week or sometimes a month. It was through these singing schools that America gradually taught its people to be musically literate for a century and a half.

James Milton Black

James Milton Black (1856-1938) was one of the teachers of such singing schools in the late 18th century. Not only was he a singing master but he also proved to be a prolific hymnwriter, composer, and an editor of numerous gospel songbooks.

James Milton Black

Description

Hymn’s Inspiration

“I spoke of what a sad thing it would be when our names are called from the Lamb’s Book of Life, if one of us should be absent.” J.M. Black

In 1896, Black together with Joseph Berry, edited the gospel songbook called Songs of the Soul. According to the hymn’s preface, it was “published in response to an urgent demand for a low-priced book especially adapted for congregational singing, revivals, camp-meetings, social services, and young people’s devotional meetings.”

And it did sell! 400,000 copies were sold within two years. Partly because of its low price and also to the high demand during the time of the Great Awakening in America.

James Black edited many other hymnals but this one proved to be one of the most successfully sold songbooks he did during his lifetime. One of the many songs included in this edited hymnals was his famous gospel “When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder.” This was a hymn he penned in his earlier years with inspiration from a girl he met named Bessie.

Bessie

In his younger years as a singing school master, Black was also a Sunday school teacher and president of the Young People’s Society of his local Methodist-Episcopalian church.

He loved working with the young people and tried to win them for Christ. One day, as he passed through an alley, he met a disheveled and ragged 14-year-old girl. She was the daughter of an alcoholic. He invited her to his Sunday school and youth group and she began to attend.

However, one day when he took roll call, the girl did not respond. Each child had to say a Scripture verse when his or her name was called. James saw a lesson in her silence. “I spoke of what a sad thing it would be when our names are called from the Lamb’s Book of Life, if one of us should be absent.”

After Sunday school, he went to his pupil’s home to find out why she had not showed up for class. He found her dangerously ill with pneumonia and sent for his own doctor. Since that was before the days of antibiotics, death was highly likely.

James returned home. He tried to find a song to fit the thought of a heavenly roll call but could not locate one. An inner voice seemed to say, “Why don’t you write one.” And that is what he did.

“I played the music just as it is found today in the hymn-books, note for note, and I have never dared to change a single word or a note of the song,” he said.

A few days later, he had the sad opportunity of explaining in public how he came to write the song when it was sung at the funeral of the girl whose absence at roll call had inspired it.

The same power that raised Christ from the dead will raise His church, and glorify it with Christ, as His bride, above all principalities, above all powers, above every name that is named, not only in this world, but also in the heavenly courts, the world above. The victory of the sleeping saints will be glorious on the morning of the resurrection.

My Life Today, 295.6

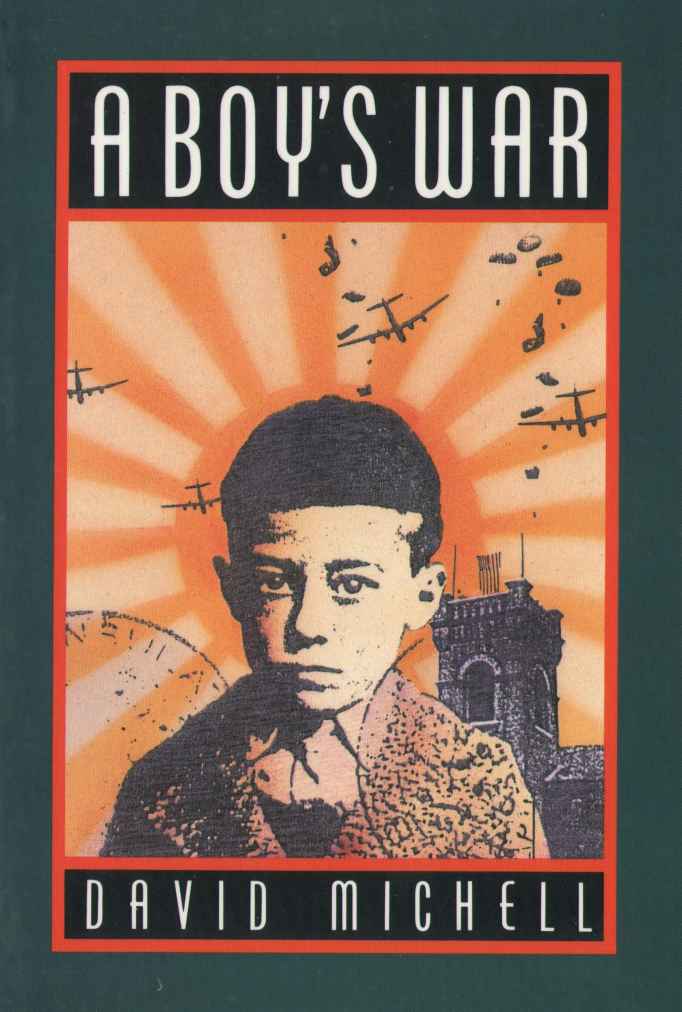

‘A Boy’s War’ and the Misapplication of This Hymn

In David Michell’s A Boy’s War, he relates the time when this song comforted a group of traumatized children in a Japanese concentration camp. On November 5 1942, the students and faculty were marched from their campus and eventually ended up in Weihsien Concentration Camp.

Among the students was Brian Thompson, who died from electrocution when he touched a bare wire one evening. During his funeral, the principal led a very solemn funeral service. They sang this hymn and comforted in the thought that although Brian had missed roll call in camp that morning, he had answered one in heaven.

Death is one of the most misunderstood subjects today. For many, death is shrouded in mystery and evokes dread, uncertainty, and hopelessness. Others believe that their deceased loved ones are not dead at all, but instead live with them or in other realms. However, in many Christian circles, the death a loved one who was known to be kind and good during their lifetime is believed to go straight to heaven. Such was the case in ‘A Boy’s War.’

But is this true? Do good people go to heaven after they die?

Scripture says that “All who are in the graves will hear His voice and come forth” (John 5:28, 29). That “David … is both dead and buried, and his tomb is with us to this day. … For David did not ascend into the heavens” (Acts 2:29, 34). “If I wait, the grave is mine house” (Job 17:13 KJV). So, no. People do not go to heaven or to hell at death. They don’t go anywhere—but they wait in their graves for the resurrection.

This is the correct view of death and resurrection as reflected in the 2nd stanza of the hymn:

On that bright and cloudless morning when the dead in Christ shall rise

And the glory of His resurrection share;

When the chosen ones shall gather to their home beyond the skies,

When the roll is called up yonder I’ll be there.

What do you think of this hymn? Let me know your thoughts in the comments section below