The year was 1670. The Pietist movement was sweeping fast across the Protestant areas of Germany. Many sermons placed an emphasis on personal religion. And at St. Martin’s church in Bremen, it was no different.

Using 1 Peter 1 as a basis of his sermon, the preacher gave a powerful call to a real spiritual rebirth, a true inward holiness.

In the midst of the congregation, a young man listened, dumbfounded and abashed. He and his friend came to church with every intention to make a joke out of the whole sermon. But as he listened, the discourse turned out to be nothing like he heard before. New, not really. But it was definitely straight, heartfelt and earnest.

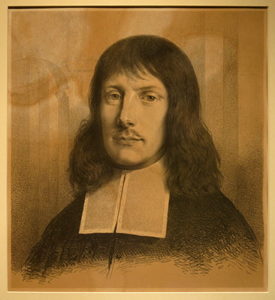

The preacher, Theodore Undereyk, a pioneer of pietism in the German Reformed Church. The wild 20-year old young man, Joachim Neander, the hymn writer for the famous hymn, “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty.”

But, let’s not get ahead of ourselves here.

Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?

Joachim Neander’s father, a Latin teacher, died when he was a teenager. This left the family bereft of a strong financial source, forcing Neander to choose a local school instead of going to one of the famous German universities.

In the school, Neander signed up to be a theology student. But his heart just was not in it. As a student, he led an immoral and lusty life. Ironically, it was not long after he gained a reputation for having a wild lifestyle. His contemporaries wrote that “his student life was spent in vanity of the mind, forgetfulness of God, and the eager pursuit of youthful pleasures.”

And so as the story goes one fine Sunday, he and two of his friends went to church not to worship, but to make a spectacle out of it. But as Neander sat and listened to the sermon, a strange conviction came to his heart and he was never the same.

Another incident that solidified this conviction was during a hunting game. He had wandered far into a steep and rocky hillside and realized that he was completely lost and in physical danger if he tried to make his way in the dark. Sensing the urgency of the situation, he prayed that if God would lead him to safety, then his future life would be dedicated to God’s service.

And we could all guess how God answered that prayer. Because Joachim Neander turned out to be one of the finest hymn writers, not only for the Pietist movement, but for the Protestant church as a whole.

The “Original” Neanderthal Man

Many of us have probably a slight clue about the Neanderthal man, a species classified by evolutionists as archaic humans. It got its name from one of the first sites where they discovered the fossils. The site was 7 miles east of Dusseldorf, Germany in a cave located nearby Dussel river in Neander valley.

You might probably be wondering why I’m suddenly talking about fossils. Well, in case you haven’t noticed, the fossil was named after Neander beacause it was found in a valley that was also named after Neander.

What a strange coincidence!

And believe it or not, we are still talking about Joachim Neander. I never changed the topic, just so you know.

Why would a valley be named after Neander anyways?

Neandertal (F.W. Schreiner), © Stiftung Neanderthal Museum

Well after his conversion experience, he got a job as a director of the Latin School in Dusseldorf. It was somehow a stressful experience for him because of the strong opposition against Pietism.

To detox himself from such a difficult situation, he would take long walks. Seeing the nature around him would seem to refresh his mind, inspiring him to write hymns. In fact, most of his hymns (he wrote 60) were written during his stint at Dusseldorf.

One spot that attracted him was in a valley near Dussel river. He would go there to hold worship services, to relax, and of course, to write hymns. He spent so much time in that area that the locals started calling it Neander Valley.

He died too young

Ten years after his conversion experience, Neander was seized with a sudden and violent bout of tuberculosis. An incurable disease at that time, he expected his death to be imminent.

Yet through his suffering, Neander’s mind was stayed on God.

Through sore coughs, witnesses at his bedside still heard him say, “Rather will I hope on, even unto death, than be lost through unbelief.”

Through a thunderstorm, he cried, “I hear my Father’s voice; would that it were his chariot-wheels, coming for me!”

When given food to eat, he exclaimed, “It is not only ‘taste,’ but ‘taste and see that the Lord is good;’ though I cannot taste this food, I can see it.”

Finally, on May 31st when the signs of death were unmistakable, the physician asked how he felt, he replied, “Now the Lord has made out my reckoning.” And then quoting from Isaiah 54:10, he says, “The mountains shall depart, and the hills be removed, but my kindness shall not depart from thee…” Soon afterwards, he gently fell asleep.

He was 30 years of age.

Two hymns

From Neander’s repertoire of 60 hymns, two have made its way to the Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal. Praise to the Lord, the Almighty (SDAH 1) and All My Hope on God is Founded (SDAH 5).

While the composer of the tune for Praise to the Lord is unknown, its tune name was called LOBE DEN HERREN, adapting the original German lyrics that Joachim Neander wrote. In the meantime, All My Hope on God is Founded was given a tune (MICHAEL) by Herbert Howells, a well-known English composer.

We are also indebted to Catherine Winkworth who did an amazing job translating these German verses to English. Without her, we would have not truly enjoyed the merits of these beautiful verses.

Who would’ve thought that a wild and carefree man would pen such great hymns? Thanks to the power of the Holy Spirit who can convict men of sin that they “…may also do good, ye that are accustomed to do evil.” (Jer. 13:23)

Enjoyed this story? Share it!

2 replies on “Joachim Neander: The Wild Hymn Writer”

How wonderful to learn of the write of these vibrant hymns – and to learn of the origin of the word Neanderthal!! Praise the Lord for His expression through His beloved.

Thank you!!! I love reading stories of beloved old hymns and the person behind them. It always makes the hymn so much more meaningful.