Pop tunes in an Adventist hymnal? Who would allow such a thing? How about James White and Uriah Smith, two of our most revered pioneers?

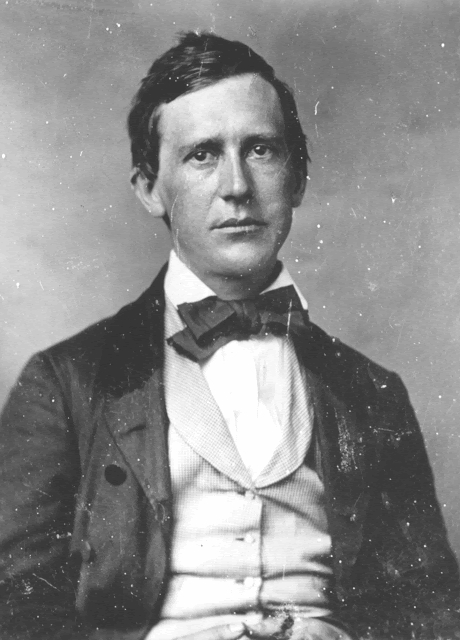

Uriah Smith had been the class poet at Phillips Exeter Academy, one of the top New England prep schools of the day. He was ready to enter Harvard University as a sophomore when he learned the good news, the gospel; and he decided instead to devote his budding literary talents to an obscure, despised religious newspaper, the Review and Herald.

Pop tune no. 1: Swanee River

Stephen Foster’s song was all the rage the year Uriah became an Adventist. The prestigious Dwight’s Journal of Music observed:

“Old Folks at Home (Swanee River)”… is on everybody’s tongue, and consequently in everybody’s mouth. Pianos and guitars groan with it, night and day; sentimental young ladies sing it; sentimental young gentleman warble it in midnight serenades,…boatmen roar it out stentorially at all times; all the bands play it,…the “singing stars” carol it on the theatrical boards, and at concerts” (October 2, 1852).

Little wonder that even after he became an Adventist, Uriah Smith had difficulty forgetting “The Swanee River.” But while Stephen Foster looked backed nostalgically to a time that never was, Uriah Smith changed this melancholy lament into a hymn of hope:

Up to a land of light we’re going —

Joys, joys are there;

Where pain and sorrow no more knowing,

We shall its glories share.

Soon we shall hail the radiant dawning

Of endless day —

E’en now the light of that glad morning.

Breaks oe’r the shadowy way.

CHORUS:

There beside Life’s flowing river

And Life’s fadeless tree,

We shall inherit joys forever,

Joys that are boundless and free.

This hymn first appeared in the Review. Then, in 1858, it was published in the supplement to Hymns for Those Who Keep the Commandments of God and the Faith of Jesus.

Why should such a song be brought into the church? Apparently many early believers often lacked even the most basic musical training and ability. They could not read music, and though they did well enough in their local meetings in the sitting room of a neighbor’s farmhouse, when they got together in larger groups for district meetings, the results were sometimes chaotic. In 1859, Joseph Clarke, a pioneer Adventist preacher, wrote:

I lately attended a conference, where brethren and sisters from different sections were gathered; and it was good to see them there. I greatly rejoiced to greet those of like precious faith; but alas! when we sang; one prolonged a quarter note, until it consumed the time of a whole note, with a hold and a swell besides. Some were singing one verse, until others had progressed pretty well into the next; and the ending word of each verse, echoed and re-echoed, each according to the different notions of propriety, which each locality administered for itself.

(Review and Herald, November 10, 1859).

In such a situation, a familiar tune could bring welcome relief.

Then, too, the popular culture of that time was not so far removed from the religious culture as it is today. The differences between Lowell Mason’s hymn tunes and Stephen Foster’s compositions were not nearly so great as the differences between the great hymns of the church today and most of the popular secular music. This practice of our church was not continued beyond those early days. It served a purpose for that time, but as musical knowledge widened, it was no longer necessary to use popular tunes.

Songs that remained popular in the secular culture, like Stephen Foster’s, quickly disappeared from Adventist hymnody in the United States. However, songs that did not remain popular with the general public were retained, and many are still a part of Adventist hymnody today.

Pop tune no. 2: Bonny Eloise

For instance, in our current Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal, we find the song “How Sweet Are the Tidings,” No. 442. The tune of this hymn was the song of the year in 1858. During the Civil War it was popular with the army bands of both North and South.

The original words were entitled “Bonny Eloise”:

O sweet is the Vale

Where the Mohawk gently glides

On its clear winding ways to the sea,

And dearer than all

Storied streams on earth besides

Is this bright, rolling river to me.

But sweeter, dearer,

Yes, dearer far than these,

Who charms where others all fail,

Is blue-eyed, bonny, bonny Eloise,

The Bell of the Mohawk Vale.

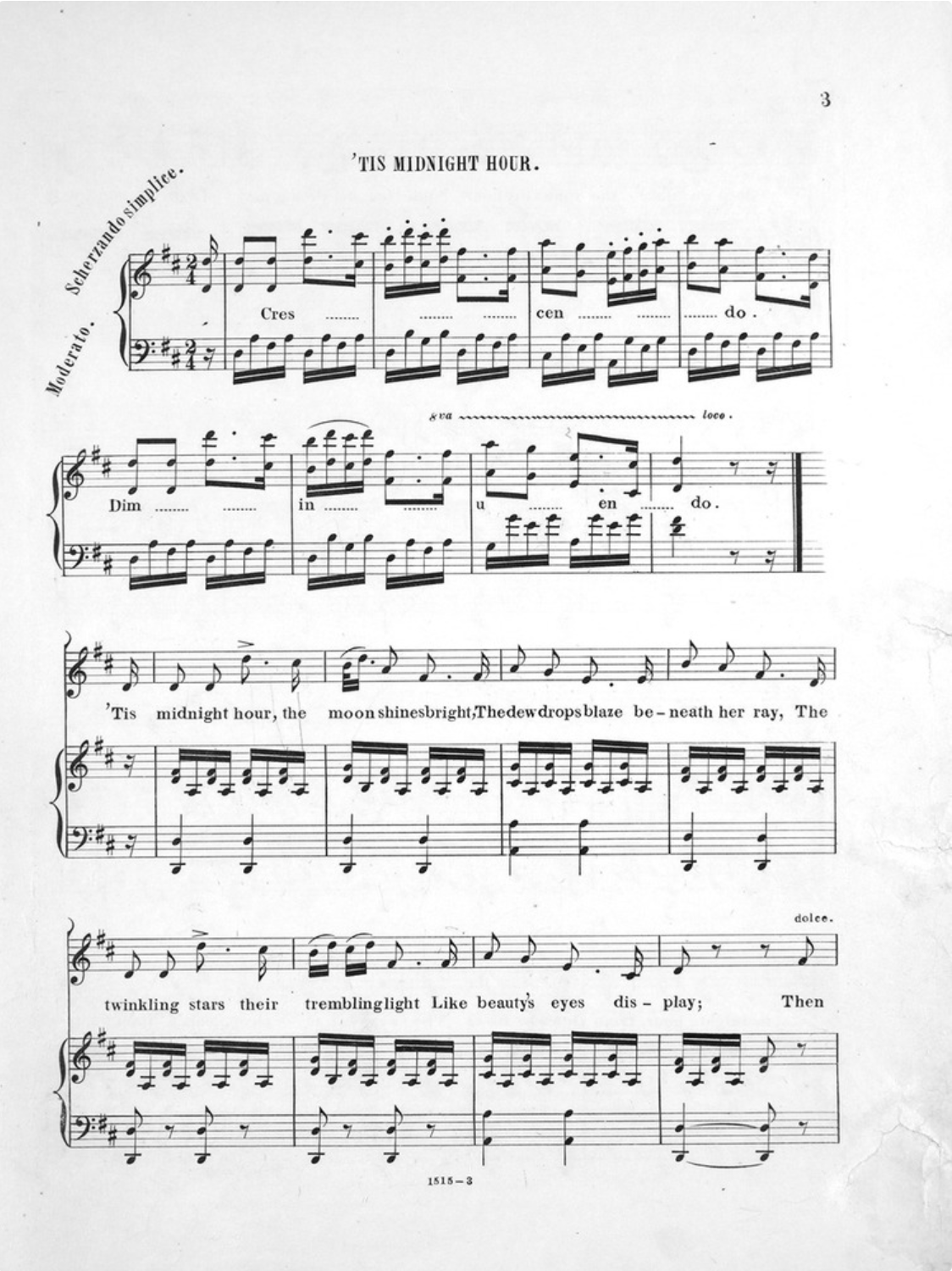

Pop tune no. 3: ‘Tis Midnight Hour

Uriah Smith’s sister, Annie, was another or our early hymn writers likely to “baptize” a secular tune for church use. She had attended the Charlestown Female Seminary near Boston, Massachusetts, before she became an Adventist, and had written poetry for popular women’s magazines of the day. When she became an Adventist and joined the editorial staff of the Review, she continued to write hymns and poems.

Back in 1843, the following anonymous song had appeared in Cincinnati:

‘Tis midnight hour, the moon shines bright,

The dewdrops blaze beneath her ray.

The twinkling stars their trembling light

Like beauty’s eyes display.

Then sleep no more, though round thy heart

Some tender dream may idly play

For midnight song, with magic art,

Shall chase that dream away.

Annie Smith transformed this typical, worthless, sentimental, mid-Victorian ditty into a hymn that is still loved and sung by Adventists: “How Far From Home?” The Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal, No. 439. Notice the similarity in the fifth line. Where the popular song has “Then sleep no more,” Annie wrote, “Then weep no more.”

Pop tune no. 4: Dixie

Of all the songs of this genre, probably the most outrageous to modern American tastes is one that, fortunately or unfortunately, never made it into and Adventist hymnal. It was, however, published in the Review, July 7, 1863, after having been submitted by Emma House, an amateur poet in Caitlin Center, New York.

We’re traveling toward a country bright,

Where all is peace, and love, and light,

Look away, look away, look away to that bright land,

We know the dangers that surround

The footsteps of the homeward bound;

Look away, look away, look away to that bright land.

CHORUS:

We’ll all fight for the victory,

And win, and win.

And when we reach that happy spot,

Our pilgrimage will be forgot

In the joys, in the joys, in the joys of God and heaven.

In the joys, in the joys, in the joys of God and heaven.

If you haven’t already guessed, these words fit the tune “Dixie.” Conditioned as we are to associate this tune with thoroughly secular ideas, we find it difficult to reap any spiritual benefit from the religious words. Back in 1863, though, this association didn’t seem to shock Review readers.

In South America, Adventist unfamiliar with Stephen Foster still enjoy singing a hymn to the tune of “Old Folks at Home.” Not great music, perhaps, but except for its difficult range, an easily remembered tune. Perhaps we could revive Uriah Smith’s version at least for campfire programs. Here are the second and third stanzas:

No earthly charm may then allure us,

Or lead astray;

Since all its faded hopes assure us,

They too shall vanish away.

In heaven only can our treasure

Be laid secure;

There only may we seek for pleasure,

Holy, immortal, and pure.

Then let no toiling heart grow weary,

Or fainting be;

Soon we’ll forget our exile dreary,

Joyous in victory.

There where our heart’s affections center,

Around the throne;

Those pearly mansions soon will enter,

And be forever at home.

(Written by Ron Graybill, who was an assistant secretary in the Ellen G. White Estate at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. This article is adapted from Insight, April 24, 1979. It was republished in Adventist Education October-November 1994 issue and is used with permission.)