“Music,” said Tschaikovsky, “is the most beautiful of all heaven’s gifts to humanity, a candle in the darkness, it calms, enlightens and stills our souls.” Music is a science and an art, and as such its contribution to our enjoyment and refinement may be immeasurably increased by our study and development of its intricacies.

The grandeur and expressiveness of music are demonstrated by the fact that the most sublime experiences in human history have been accompanied by music. This marks it as the supreme expression of the height and depth of human emotion.

God told Job that at creation the “morning stars sang together.” After the deliverance at the Red Sea, Moses sang in such majestic language that its inspired theme is worthy to be sung on the sea of glass. At the dedication of Solomon’s temple, the dwelling place of God among men, thousands of Levites arrayed in white linen with cymbals and psalteries and harps, one hundred and twenty priests with trumpets, and a great trained chorus, accompanied the orchestra. Holy Writ says the harmony was perfect, for “the trumpeters and singers were as one, to make one sound.” Then it was that the house was filled with a cloud, so much so that the priests could not stand to minister because the glory of the Lord filled the house. On the night when Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the hills of Judea were flooded with the music of a multitude of the heavenly host praising God.

The earthly pilgrimage of man has been marked by a constant effort to approach the music of heaven, but the history of music was a slow, almost painful development toward the attainment of heavenly music.

In the wilderness, Israel chanted the commandments to the sound of instrumental music, so we are told by the Spirit of prophecy. Simple in form though the chant may be, their thoughts were uplifted from the trials and difficulties of the way. Concerted action brought about order and unity and the people were brought into closer communion with one another. Chanting is a simple form of music, for its rhythm is determined by the text of what is sung and, the only way to keep religious music pure was to preserve it in such a form.

In the three centuries before Christ, known as the Hellenistic Age, when the influence of pagan Greek civilization became universal, it was difficult to preserve the purity of thought in music, for the immoral Greek feasts were accompanied by vocal and instrumental music of far more appealing beauty as the senses were concerned.

When we reach the Christian Era, we find, too, that early church music was dissociated severely from the music of the pagan world. In fact, during the third and fourth centuries after the Apostolic Age, and until the development of the papacy, the history of church music was closely paralleled by the system of church government and its development from the democratic apostolic system to the hierarchal organization of the medieval church.

As we approach the setting up of hierarchal forms of church government, more emphasis on ritualistic music became characteristic. The laity ceased to share in the music of worship. The Council of Laodicea (4th century) forbade congregational singing in the churches. The use of instruments in worship likewise ceased altogether. It was St. Jerome who declared “a Christian maiden ought not to know what a lyre or flute is or what it is used for.” The purpose of this was to avoid entirely the very appearance of pagan music in worship, and especially Greek music, for it was realized how easily music might become debased by rhythm, as we see so well illustrated today by some modern music.

But plain unison singing could not satisfy the heart of man forever, just as today many sing a bass or tenor even before they can read music. So it came about that by the end of the 10th century a second voice was added to the monotonous chant, to give a little color to religious music.

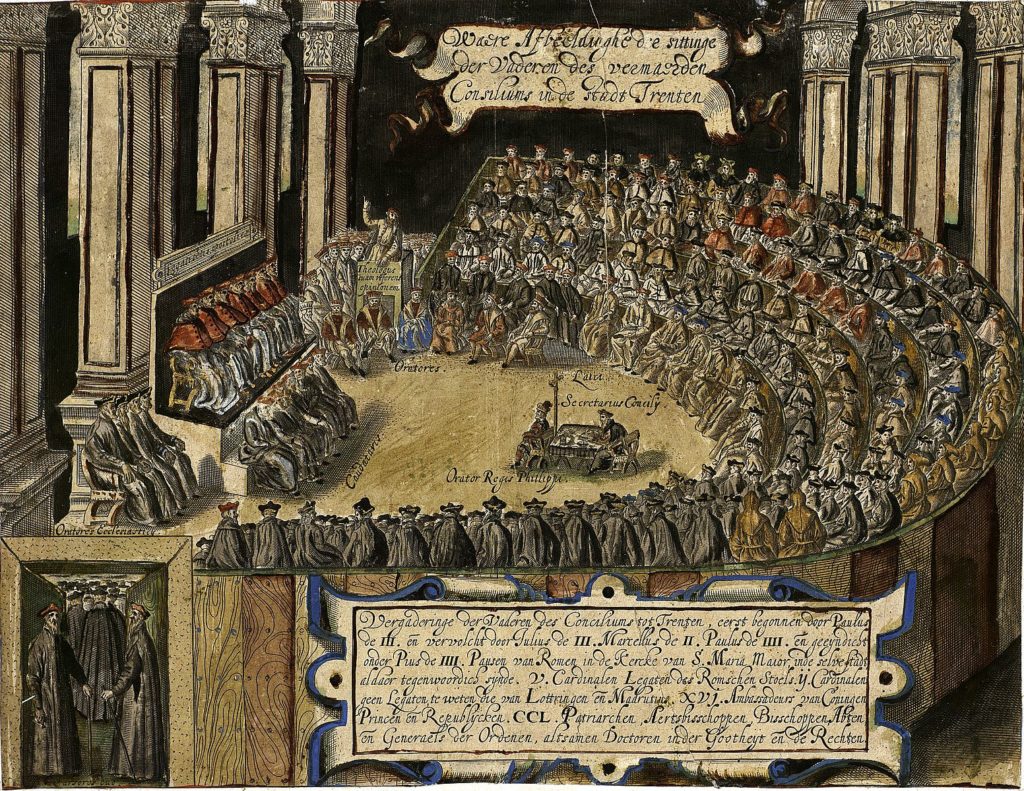

Under the influence of the Renaissance and the freeing of the very spirit of man, even church music became so flowery and contrapuntal in form that the words could not even be understood, with the result that the Council of Trent threatened to anathemize all such music and demand a return to the simple chant of unison singing.

To save something of what had been attained in the enrichment of church music, the famous Palestrina came to the rescue and presented to the Council, so it is believed, his restrained but beautiful music. Although it was contrapuntal, it was nevertheless so simple and beautiful that it received the blessing of the Roman Church. This important Council of Trent in the 16th century fixed the pattern of much of Catholic practice and belief for all time to come, and it is interesting to note that in the field of music, all liturgical forms of worship, including the Catholic, preserve a relatively simple form of religious music.

Here we come to an important point of change, for with the Protestant Reformation, we see an altogether new emphasis on the hymn, sung by the people, in the language of the people, as a proof of emancipation. In England, the Lollards, followers of Wycliffe, the Morning Star of the Reformation, introduced the first of this new form of church music two centuries before Luther’s day. These hymns were based mostly on folk music but usually were modified in some respects as religious music. It is interesting to note, however, that we have hymns in our church hymnal that were purely secular at one time. If we knew the original words, we would probably not enjoy them at all as hymns, just as many feel about Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” not recognized even by the Catholic Church as music of worship.

It remained for Luther, however, to make such hymnology a thing militant, to free the hearts of man by the power of music. The very

spirit of the Reformation was carried on the wings of hymns based on the folk of the people. Many of Luther’s hymns served their purpose and then died, as do many hymns today, but one at least will live forever as the battle hymn of Protestantism, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.”

With the Wesleyan revival in the 18th century, a new and deeply emotional form of music was born, and today we still sing the beautiful hymns of the Wesleys, Isaac Watts, and others. During the 250 years since then, hundreds of hymn writers have given us a wealth of hymnody.

Under the impetus of various revivalist bodies of the past century, a new type of religious music has arisen, a type of music that is as varied in merit as it is in style. The Pentecostal bodies of the 30 or 40 years have popularized an extremely emotional type of gospel song. They are entirely sincere in employing music that is largely secular, even though the words may be sacred. Sincerity about music does not necessarily make it right, for the most sincere are frequently the most misguided in other things as well as in music.

(To be continued)

The following article by Wilhelmina Dunbar is taken from the March 15, 1969 issue of the Trans-Africa Division Outlook. The original can be found at the Adventist Digital Library website.

Photographs in this post are not included in the original publication of the article.

Like this article? Share it!