The execution of Huss had kindled a flame of indignation and horror in Bohemia. It was felt by the whole nation that he had fallen a prey to the malice of the priests and the treachery of the emperor. He was declared to have been a faithful teacher of the truth, and the council that decreed his death was charged with the guilt of murder. His doctrines now attracted greater attention than ever before. The Great Controversy, 115.

After Huss’ death, his followers, later known as Hussites or Bohemians continued to wage a war against the papacy. But as years passed and with continued persecution without and betrayals and dissensions within, the Bohemians crumbled. Some of them began to compromise on certain doctrinal points yet others stayed faithful.

Those who remained faithful were forced to find refuge in isolated woods and caves. As they steadily grew in number, they organized and assembled themselves together and began to take on the name “United Brethren.” By Luther’s time, they had about 200 churches scattered all over Bohemia and Moravia (both part of the present-day Czechoslovakia belonging to the Czech Republic).

They enjoyed comparative rest until the “Day of Blood”. On that day, a number of Bohemian and Moravian members of the United Brethren were beheaded and imprisoned. A number were also sent to mines and dungeons. Their churches were closed, their schools destroyed, their Bibles, hymnals, and histories burned.

These events forced many of the Moravians to flee to Protestant areas, which at this time was in Germany (incidentally where Luther made waves many years ago regarding his 95 Theses). One group of family somehow managed to make it to Saxony, where they settled on the land belonging to a rich young ruler, Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf. Or Count Z, as we will fondly call him in this article.

The Rich Young Ruler Said Yes

For 38 years, the males of the Zinzendorf family bore the title “Count”, which denoted a high-ranking status among the nobility. Among many other responsibilities, they were mainly known to accompany the emperor or represent the emperor as a delegate to different parts of the country as well as foreign lands. Thus, when Nikolaus Ludwig was born, he inherited at birth the name Count Zinzendorf.

Not only were the Zinzendorfs known as VIPs, but they were generally known to be a God-fearing Lutheran family. At birth, Count Z’s mother’s prayer involved two important things: that he walk blamelessly in the path of virtue and that this path be fortified with the Word of God.

Six weeks after Count Z’s birth, his father died of tuberculosis. Then his mother remarried when he was three. He was then left at the care of two other women, his Aunt Henrietta and his grandmother Lady Gersdorf, who brought him up in a pious atmosphere.

The sincere spiritual nature of Count Z was manifested early in life. Many times, he would be seen writing love letters to Jesus and tossing them out of the window of the castle tower.

Another story was told of the time when Swedish soldiers burst into the castle where he lived, and they were surprised to see him, a six year-old boy at that time, doing his customary devotions, praying, Bible-reading, and hymn-singing. They were so moved by this spectacle that they left the castle with a renewed change of heart.

At 10 years old, he bid childhood goodbye and moved to Halle where he spent the next six years in formal education. At that time, Halle was known as the center of German Pietism. It was also where August Francke, one of the staunchest Pietist disciple, lived and worked. Incidentally, Count Z would very often cross paths with Francke as he attended the school where this renowned Pietist taught.

While Count Z proved himself to be apt in many of the subjects taught in the school, his mind was more inclined to things that were not entirely academic. His diary bore testament of many events and experiences that impressed his young mind, many of which were spiritual in nature.

One experience that stood out to him the most was the tour he spent in an art museum in Dusseldorf. Basking in the beauty and sadness of Domenico Feti’s Ecce Homo (Behold the Man), he noticed an inscription below it – “I have done this for you; what have you done for me?” Deeply touched, Count Z said to himself, “I have loved Him for a long time, but I have never actually done anything for Him. From now on I will do whatever He leads me to do.”

Upon reaching 21 years of age, Count Z purchased from his grandmother the estate where he grew up as a child. He also opened his apartment for informal religious meetings and soon attracted a group of like-minded believers. This meetings opened up longings in his heart to form a Christian community where the persecuted can find refuge.

This prayer was answered when a lone Moravian knocked on his door, seeking an asylum.

The man identified himself as Christian David. He had heard that Count Z was allowing oppressed Moravians shelter and protection on his land. Three years later, Count Z finds himself with 90 other Moravians living in his huge estate. A year later, the population reached to 300. This place came to be called Herrnhut, meaning “under the Lord’s watch”.

Musicality of the Moravians

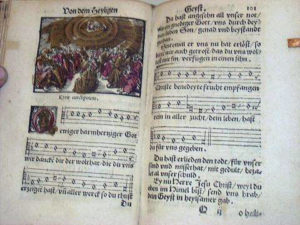

Count Z showed musical gift early in his life. Gifted in poetry and a lover of song, writing hymns was obviously of second nature to him. This particular talent bloomed in Herrnhut where he was able to actively cultivate an appreciation for the spiritual power of hymnody.

One particular musical practice attributed to Count Z was a unique worship service called Singstunde. One person is made in-charge every time. His general responsibility was to carefully select individual stanzas from various hymns in such a manner that they would develop a perfect chain of truth as the singing progressed.

The congregation, which was so well-versed in the hymnal, would chime in with the leader before he even reached the end of the first line of each stanza. The historian wrote that in many of these occasions, there was no need to announce what hymn to sing. Everyone knew each hymn by heart.

They know their hymns so much that even though several hymnals were published by this growing Moravian congregation, you would be surprised to find that these hymnals were not used at all in the worship services. Not because the hymnals were useless. It only reflected the Moriavians’ deep conviction that a hymn must be memorized in order to express adequately the individual’s Christian experience.

Hymn-singing also played a part in the mundane day-to-day at Herrnhutt. To tell the time, the designated timekeeper would sing a hymn at every hour.

In all of Christian history, the Moravian church was known to give special prominence to hymn singing never before seen in other religious sects. One unforgettable worship service that Count Z would retell over the years was when they bade farewell to their first missionaries. That evening, around a hundred hymns were sung.

Count Z would write around 2000 hymns that reflected piety and love for Jesus. Sadly however, not many of his works have found their way into the hymnals of other churches. Two hymns profoundly affected John Wesley which he translated in English and are included in the current Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal.

Untameable growth from seeds of persecution

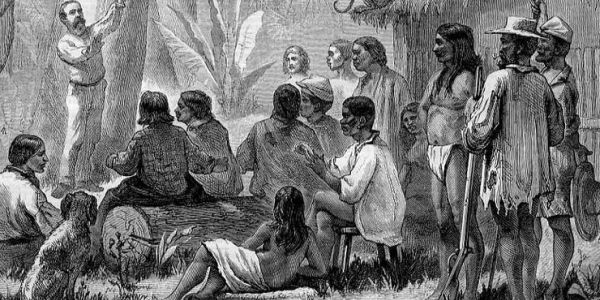

The Moravian Slaves, a popular story about Christian Missions concerning Johann Leonhard Dober and David Nitschmann, describes how these two young Moravian Brethren from Herrnhut, Germany were called in 1732 to minister to the African slaves on the Caribbean islands of St. Thomas and St. Croix.

As the Moravian church grew they began to expand their work in regions beyond. Starting from the Caribbeans, they worked their way from many areas of the West Indies, Greenland, Lapland, Persia (now Iran), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), East Indies (Indonesia), Australia, South America, Africa, and North America.

Hence it was also through the work of the Moravian brethren that John and Charles Wesley, founders of the Methodist church, came to know Christ. Personally, this provides a very interesting point of reference for me as a Seventh-day Adventist since many Adventist pioneers came from the Methodist church.

Indeed, despite the many lives sacrificed, the “dawning of that day which Huss had foretold” blossomed in full.

—–

References

The Moravians and Their Hymns. (1982). Christianity Today/Christian History magazine (US). Retrieved from http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-1/moravians-and-their-hymns.html

The Rich Young Ruler Who Said Yes. (1982). Christianity Today/Christian History magazine (US). Retrieved from http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-1/zinzendorf-and-moravians-from-publisher.html

White, Ellen G. “Huss and Jerome.” The Great Controversy between Christ and Satan: The Conflict of the Ages in the Christian Dispensation. Mountain View, Calif: Pacific Press Pub. Association, 1950. 97-119. Print.

Wylie, James Aitken. The History of Protestantism (1878). 3 vol. Cassell & Co.: London, 1899. Print.

Like this article? Share it!