“I’m a Pilgrim and I’m a Stranger” was a written by a woman who’s life was beset with tragedies; she lost sister, brother, son, and husband in the span of a few years. Instead of getting depressed and hopeless, she turned her attention to prayer and writing and with her words inspired many others.

She wrote many hymns, poems, articles and stories. She sold volumes of them, and one of those hymns is the song we’re learning in this post. This particular hymn encouraged many faithful believers, particularly the alienated Millerites who were feeling isolated from their family, friends, church mates and work mates because of their peculiar faith.

It is truly a blessing when someone else’s tragedy becomes someone else’s encouragement.

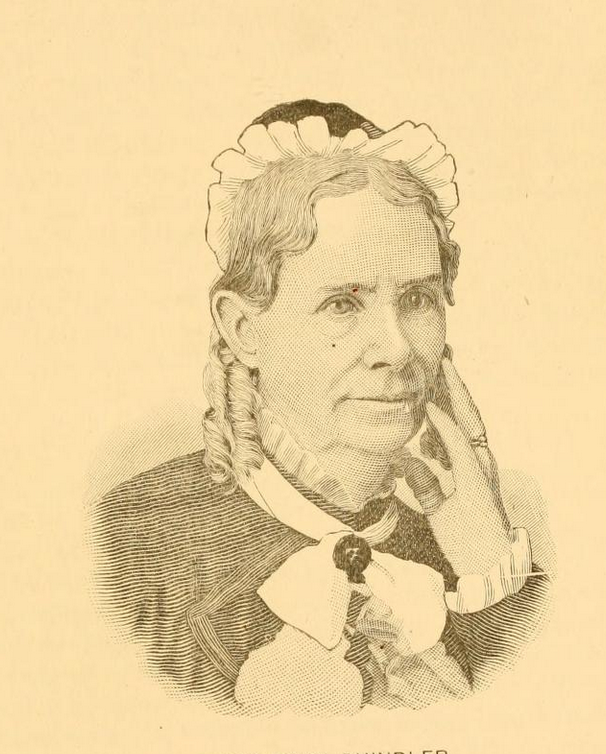

Mary S.B. Dana: Early Years

Mary is recognized in history books as an American poet and writer from the Southern United States. She was a prolific contributor to popular magazines and periodicals and known as a successful hymn writer as well. Her writing talents may be attributed to the fact that her father, Benjamin Palmer, a pastor for the Independent Presbyterian Church, was an author himself as well.

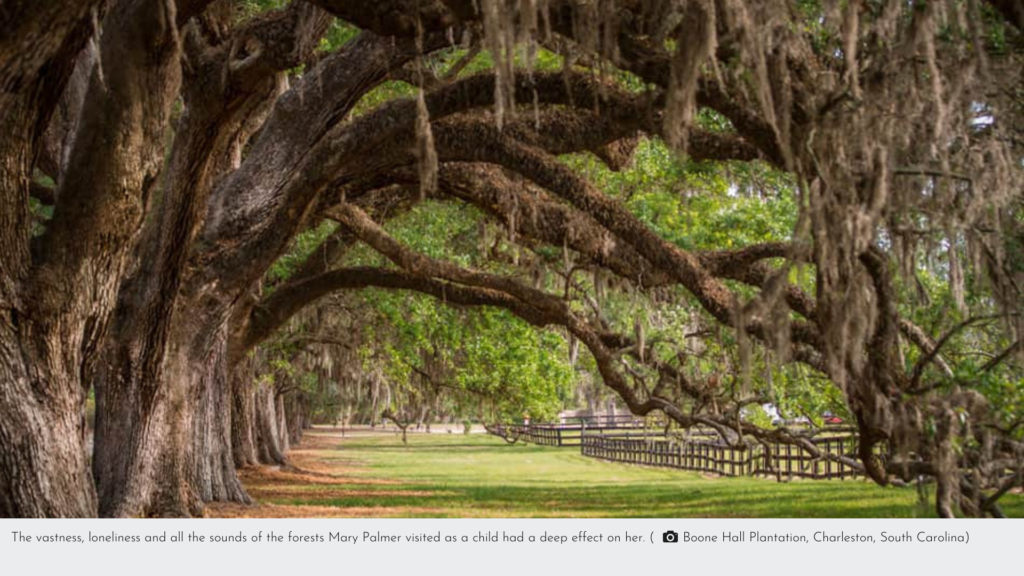

She was born in Beaufort, South Carolina in February 15, 1810. Four years after she was born, her father received a call to pastor in Charleston to a congregation of mostly planters — people who spent their summers in the city, and their winters in their plantations. Mary would reference to this period of her life as a “delight” and that she would usually anticipate Christmas holidays at these plantations where she and other children felt “released from all our city trammels, running perfectly wild, as all city children were expected to do…” Aside from the playing and romping they did, Mary also recalled:

“It was during these delightful rural visits that what little poetry I have in my nature was fostered and developed, and at an early age I became sensible of something within me which often brought tears into my eyes when I could not, not for the life of me, express my feelings.”

Female Prose Writers of America (Hart, 1857), p.154

She was also exposed to the best of the Southern and even Northern society, thanks to her parents and their connections. Her schooling was first via a private tutor, then in a seminary, first in a neighboring town called Wethersfield but she only lasted there for 6 months. She was transferred to a young ladies’ seminary in Elizabethtown, New Jersey hoping to remain there for 18 months, but only lasted for 6 months as well. She then transferred to another seminary in New Haven, Connecticut and apparently stayed several months there as well.

Young, Childless, and Widowed

On June 19, 1835, she became the wife of Charles E. Dana. She accompanied him in his travels to New York where they stayed eventually stayed for two to three years. During this time, she would occasionally write little pieces of poetry but did not really publish any of them.

In the fall of 1838 she travelled with her family including her parents towards the West. A year before this move, a little boy was born to her whom she named Charlie. They were heading towards New Orleans and while in that city received news that her only brother, who was a physician himself was sick and deteriorating rapidly. Her sister had died a year ago from tuberculosis, just a week after the birth of her son and now the news about her brother filled them all with sadness. Unfortunately, the letter came too late and when her parents tried to visit him in Alabama, he had already been buried for several days.

Without her parents, they continued their journey towards the West and embarked on a steamer in St. Louis. They remained in that steamer for six weeks and alighted in Bloomington, Iowa. They were so pleased with how the place looked that they decided to tarry and even spend the summer there. There were only about 300 people and everyone seemed healthy, but apparently that summer proved to be different. There has been a drought and the Mississippi river was quite low. Hence, there was prevalence of congestive fever (or what we now call malaria) in all of that region.

Mary was the first one to contract the fever. She had scarcely recovered when little Charlie became alarmingly ill. Even the only experienced physician in town was ill so they were already under a serious disadvantage. Charlie hang on for dear life for about two weeks and then died. Her husband Charles contracted the same illness and died two days before Charlie. Mary wrote in a letter to a friend,

“Nothing but the consolations of religion could have supported me under this double bereavement. Left entirely alone, thousands of miles away from every relative I had on earth, there was no human arm on which I could lean, and I was to rely on God alone. It was well, perhaps, for me, that I was just so situated. It has taught me a lesson that I have never forgotten, that our heavenly Father will never lay upon us a heavier burden than he will give us strength to bear.”

Female Prose Writers of America (Hart, 1857), p.156

Writing Again

She had written actively before marrying Charles but the domestic life gave her a little time to write anything worthy of publishing. After the death of her husband and son, she found a renewed interest and energy in literature and writing again. Also fond of music, she found herself adapting sacred words to a song that was pleasing to her. Her parents encouraged her on this and after gathering together a number of adaptations, she was advised to print them for her own use as well as her friends.

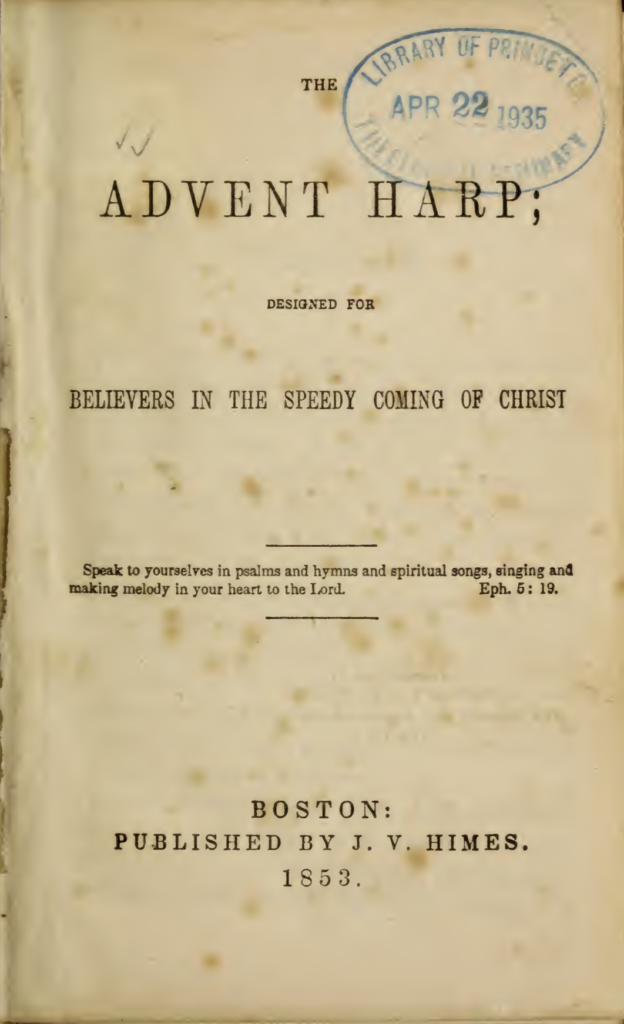

This project thrived and she decided to publish it, not only the words but the music as well. In 1841, The Southern Harp was made available to the public for the first time.

She now focused most of her energies in writing. The theme of her writings banked heavily on affliction. The same year, she published a volume of poems entitled The Parted Family, and other Poems.

At the request of her publishers, she wrote another volume similar to Southern Harp, but with the title The Northern Harp. Both the Southern and Northern Harp volumes succeeded very well, making it a very profitable venture. She also wrote prose and tales in the following years and from these gained much success.

She remarried years later to Rev. Robert Schindler and was known to go from one belief to another, searching for truth. Her latest publications were a contribution towards spiritualism. She died at Nacogdoches Texas in 1883.

A favorite hymn among the Early Adventists

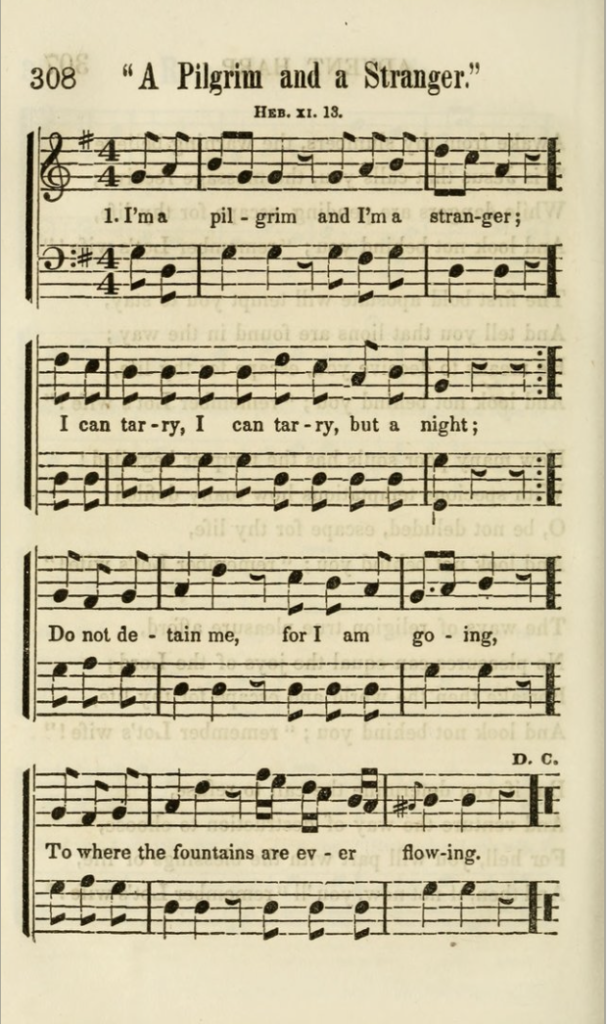

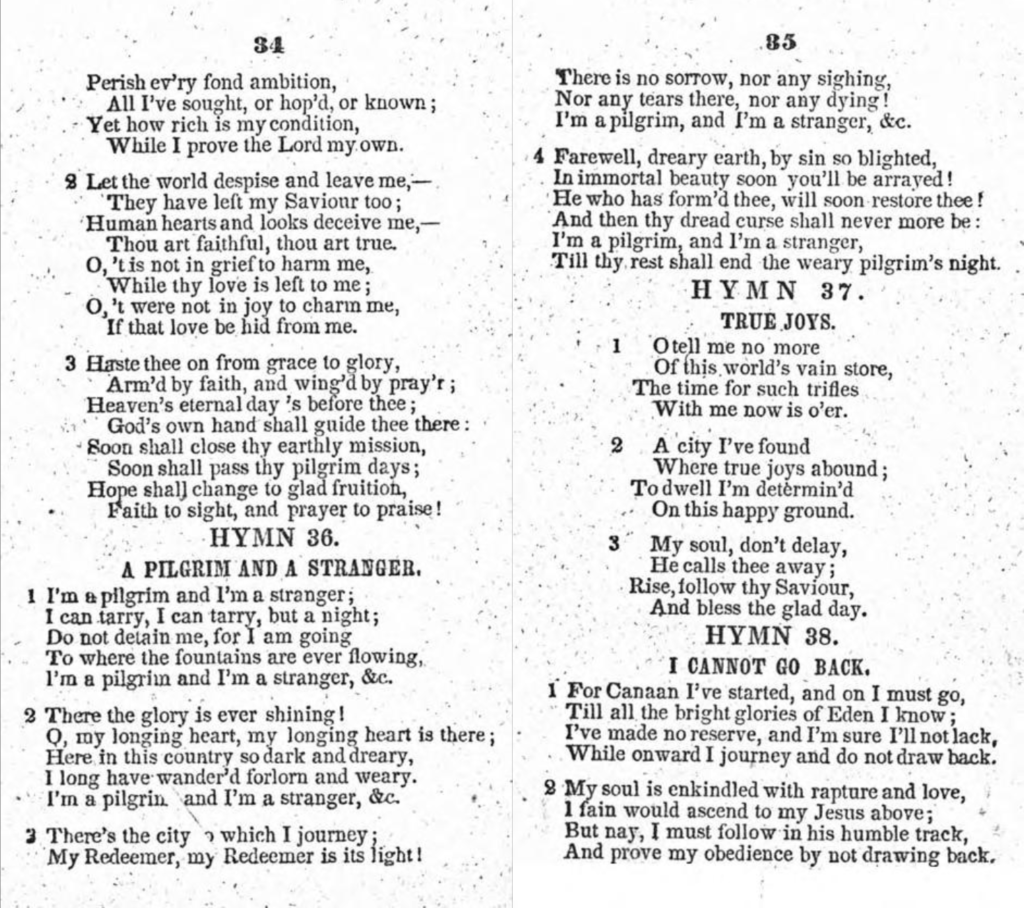

“I’m a Pilgrim and I’m a Stranger” is a poem written by Mary S. B. Dana in 1841. According to the Companion to the SDA Hymnal, she was involved with the Advent revival under the preaching of William Miller at one point and wrote this hymn.

J.V. Himes, the main man that helped Miller get into as many churches as much as possible in the cities so he can preach the Advent message also compiled hymnals so that the songs would match the messages. He included this hymn and had become a favorite among the pioneers.

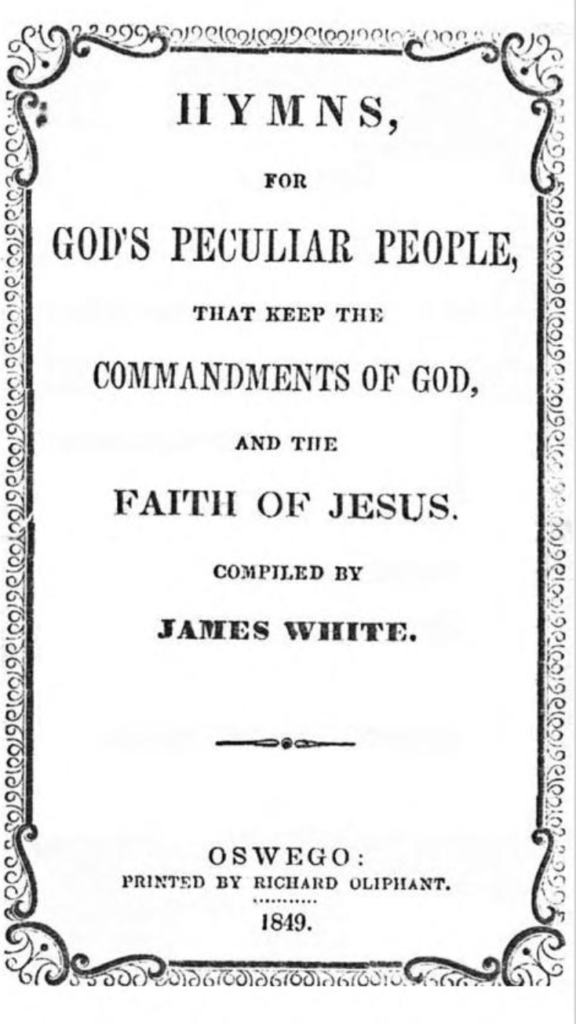

James White also included it in his 1849 hymnbook entitled Hymns for God’s People That Keep the Commandment of God and the Faith of Jesus.

Ellen White, his wife, recalled an instance when James went through the streets of Brunswick, Maine. He came back and had a bag upon his shoulder with only a few beans and a little meal and rice and flour to keep them from starvation. When he entered the house he was cheerfully singing, “I am a pilgrim and I am a stranger…”

Ellen remember herself saying, “Has it come to this? Has God forgotten us? Are we reduced to this?” James lifted his hand and said, “Hush, the Lord has not forsaken us. He gives us enough for our present wants. Jesus fared no better.”

The song has gained attraction for the Millerite Adventists because the image of being a pilgrim is definitely something they can relate to. James Nix wrote in the Early Advent Singing, a collection of 52 early Adventist hymns, that “Several of the hymns that were sung by the Millerite Adventists spoke of the feelings of alienation that they felt toward this world as they looked forward to meeting their soon-returning Lord.” This hymn was close to home for them especially after the disappointment of October 22, 1844. Also, it helped them to express their feelings of isolation as they began to keep the Sabbath while almost every churchgoer around them kept the Sunday.

“I’ll give you a quarter of a dollar for it!”

Another interesting story about this hymn was written by Joseph Bates in his Autobiography, published in 1868. Joseph Bates is a retired sea captain who had become a Millerite preacher. On one of his evangelistic meetings in February and early March of 1844 at Maryland, he had his companion Heman S. Gurney, known as the “singing blacksmith” sing this hymn. It happened that several slaves came to hear the preaching and singing.

Bates wrote further: “The slaves at the meeting seemed delighted with the Advent hymns. They heard Brother Gurney sing the hymn ‘I’m a Pilgrim and I’m a Stranger.’ One of the Colored men came to our lodgings to beg one of the printed copies. Brother Gurney had but one. Said he, ‘I’ll give you a quarter of a dollar for it.’ Probably it was all the money the poor fellow had. He lingered as though he could note be denied. Brother Gurney then copied it for him, which pleased him very much.’ (p. 286).

Learn the hymn

Printables, piano accompaniment, hymn text and other tidbits are all available in this site.

Do we still lead our lives as pilgrims on this earth?

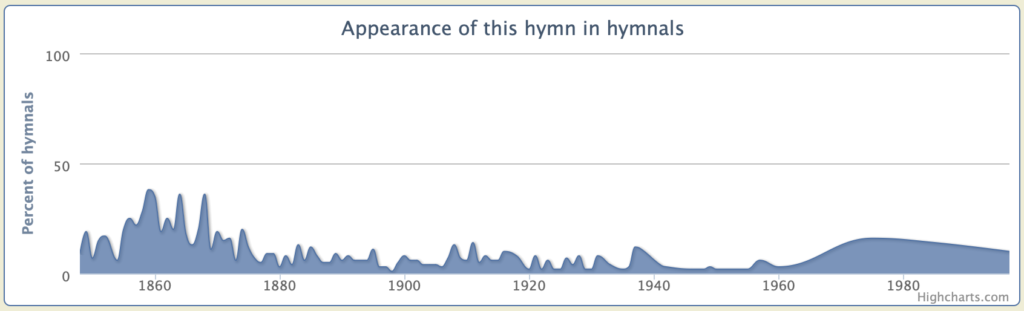

This hymn is still included in the current Seventh-day Adventist hymnal (International Edition) but only includes 3 of the 4 stanzas that originally appeared in James White’s 1849 Hymns for God’s Peculiar People. However, this hymn is rarely, maybe never sung in most Seventh-Day Adventist churches. Of course this is a biased opinion but every other Adventist I’ve asked will say no when I ask them, “Do you know this hymn and do you recall singing this in the church?”

Because hymns are usually a reflection of the messages we hear at church, would it be bold to assume and make a theory that our message does not emphasize our pilgrimage on earth anymore?

With our lives we should honor Him, and with pure and holy conversation show that we are born from above, that this world is not our home, but that we are pilgrims and strangers here, traveling to a better country.

Early Writings, p. 113.1