DATELINE: Rochester, New York, 1853: It is 2:00 in the morning, and a young man, working by the light of a simple oil lamp, is daubing ink on an inking board.

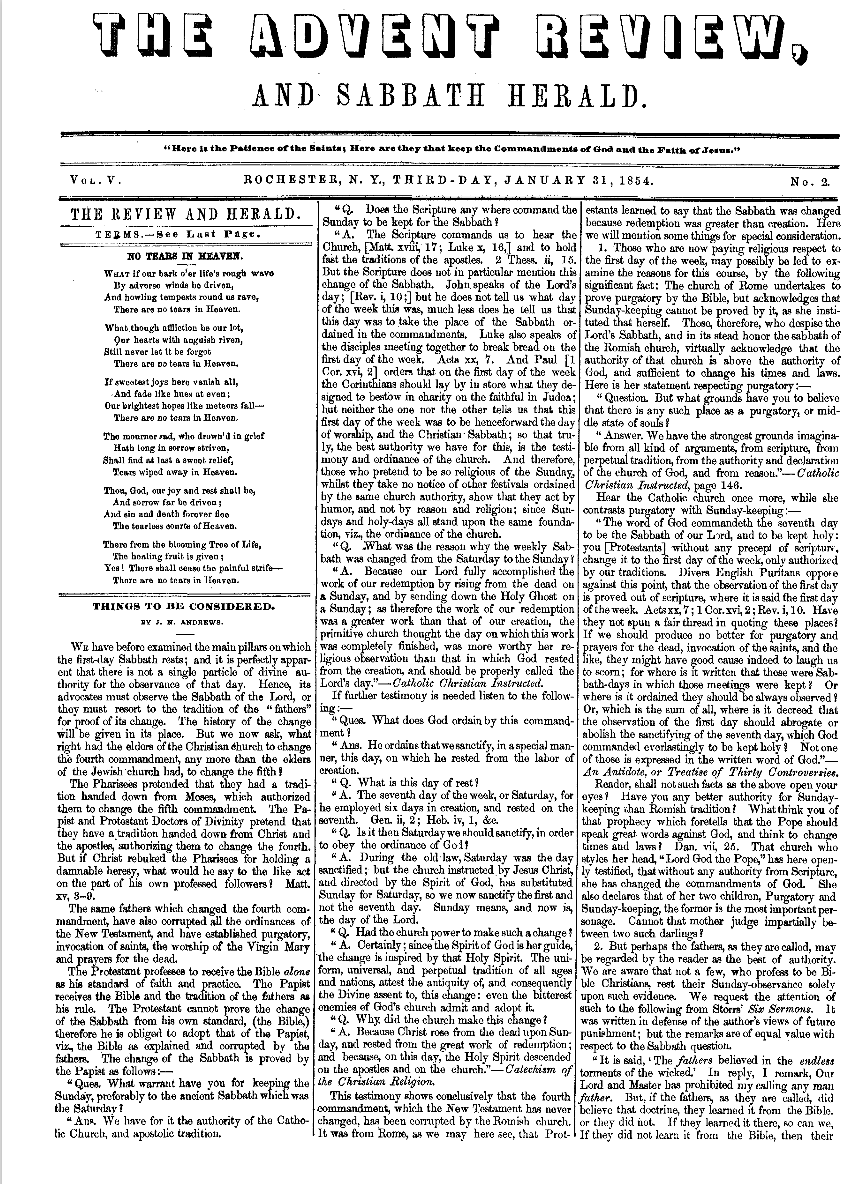

When the right amount of ink is evenly applied by a roller to a heavy tray of type, the wooden tray or galley is positioned beneath a cumbersome press that will bring pressure down on the type. Before the contraption moves, a sheet of paper is laid over the galley. The lever is then firmly brought down, and hundreds of sharp black characters spring to life on the vellum sheet.

The printer straightens his back, rubs the cold out of his fingers, and prepares to work with another galley, heavy with type. But before doing so, he hands the galley proof to 14-year-old Warren Bacheller. Known as a printer’s devil by the pressmen, the apprentice runs through the dark snow-covered streets with a folder of proof sheets. Reaching the big house on Mount Hope Road where he and his fellow workers sleep and eat, he feels his way up the dim unheated stairway and pushes the folder under a closed door. James and Ellen White, with sons Henry and Edson, are asleep. Standing outside the Whites’ door, he detects the acrid scent of a burned-out wood fire. It is only a memory of warmth, but it will have to do. An ice-cold bed awaits him.

Early Risers

The Whites will not sleep late. Ellen does much of her writing by candlelight before the dawn, while James does his best work between 9:00 and 12:00 a.m; both are early risers. They carefully read the galley proofs, correcting phrases, adjusting words, before joining other members of their staff for breakfast and morning worship. After devotions they receive the additional galley proofs produced by Luman Masten, the faithful printer, before he turned in at 3:00 a.m.

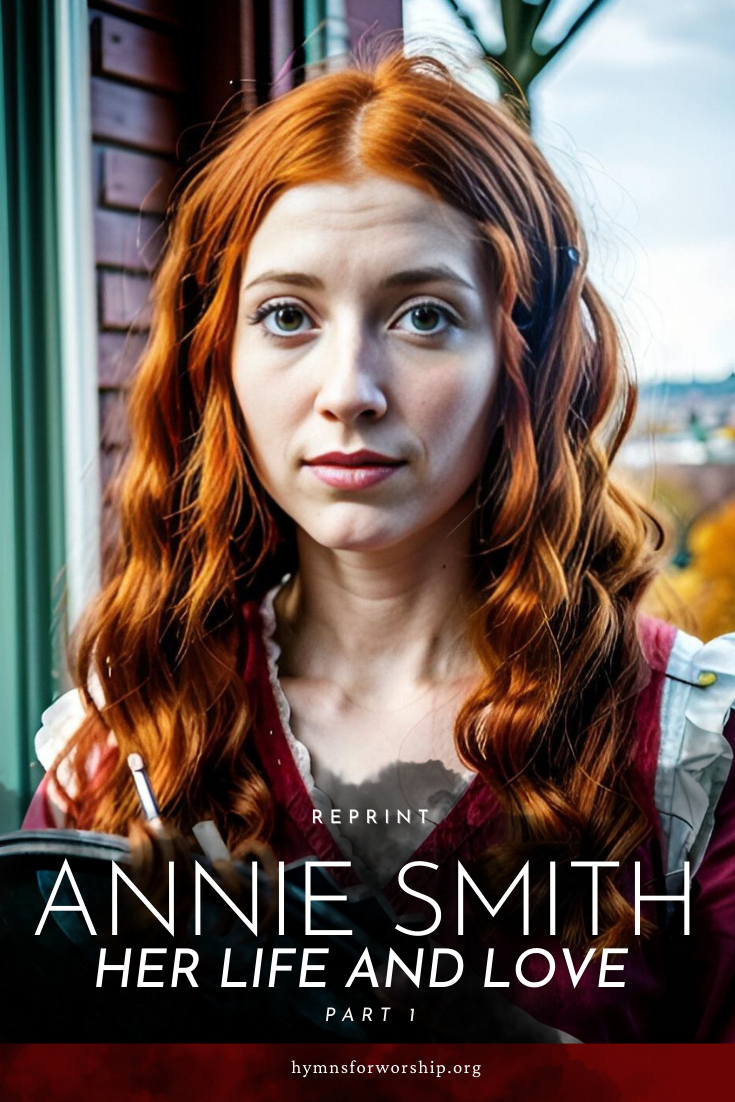

James hands the precious galley sheets to Annie Smith, a young editorial assistant, who checks them for typographical or grammatical errors. If she sees no significant changes that require consultation, she, in turn, gives them to young Bacheller or his fellow apprentice, Fletcher Byington. The copy is hurried to the pressmen for correcting. Typesetters, used to reading backwards, set the small metal letters in reverse order.

Edited galleys keep the handpress clacking for three days, each tray of type producing four pages of the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald. Two thousand copies emerge from the handpress for each issue. But the job is far from finished. While typesetters, assisted by the two apprentices, compose the next issue, each of the 2,000 copies must be folded, stitched, and trimmed. In a back room of the large house on Mount Hope Road, John Loughborough punches holes for the sewing, then passes the pages over to George Amadon, who stitches them together. Uriah Smith trims the edges with his penknife, for the magazine owns no paper cutter. Years later Smith would recall, “We blistered our hands in the operation, and often, the tracts in form were not half so true and square as the doctrines they taught.”

What motivates these young adults? What keeps them working day and night in a poorly equipped operation that pays virtually no wages? If you were to ask them, they might tell you of the vision given to one of their number. Before the press ever began to clank, before James White produced the first copy of Present Truth in 1849, Ellen White had seen the Advent truths reaching to distant parts of the globe.

The thought that the little press at Rochester might have a worldwide impact seems preposterous to those outside the team. But these young adults have a dream or more accurately, it has them! We can almost hear the young Ellen White as she leads in morning prayers, her voice warm and gentle, but firm. “It was in a vision five years ago that I saw it,” she says slowly. “I was shown that the message as streams of light would go clear around the world.”

The female members of the staff help to address each publication. This is also done by hand, using sharpened quills or simple ink nibs. The completed copies are tied in bundles and, usually on Thursday, packed into a cart or wheelbarrow for transit to the post office. There is no shortage of work, no underemployment. Sometimes the women get more than their share of the work. But complaints are few: courage is high.

While the Review and Herald is their principal product, the workers at Rochester also publish the Youth’s Instructor, hymnals, and a variety of tracts presenting the distinctive beliefs of Sabbathkeeping Adventists. After three years of operation the self-supporting company offers some 30 publications for sale to the public.

The Whites also maintain a lively correspondence with believers from Maine to Iowa as well as with the Review’s contributing authors, scattered nearly as far. In addition there are weekly speaking appointments in upstate New York, some of them requiring a day’s travel by carriage.

Financing the publishing work is a constant problem. The Review and Herald is sent free of charge to all who request it, and depends on donations from its readers. One week, however, the press is out of paper, and there is no money to receive the COD order at the post office. James White is on the verge of panic. Without paper, the entire business will shut down. Quietly Ellen retrieves a sock from her kitchen. Coins to pay the large bill are poured out on the table.

“Where did you get it?” James asks in amazement.

“Saving for emergencies,” she explains with a smile. Week after week she has saved a small amount from the group’s meager food allowance.

James and Ellen are at the nerve center of the ceaseless activity. In vivid visions Ellen is instructed that James must “write, write, write!” But a difficult snag develops. Joseph Bates, the respected senior among the Sabbath-keepers, advises against regular weekly or monthly periodicals. The older man maintains that individual leaflets, each comprehensively presenting a doctrine or issue, are preferable. The plan is flexible and economically feasible: the counsel makes sense. But Bates’ letter discourages James. He is ready to quit, but Ellen urges him on. Though the magazine is mailed twice a month now, she says, she has been shown that it must become a weekly publication. Not less, but more!

“But we have insufficient funds now,” James protests, “and difficulties enough meeting deadlines!”

“Yes,” she says, “but I was shown that the Review should be received each week. People are asking for it. Send it out! Readers will contribute the necessary funds.”

James is reassured, and trusting in the authenticity of the guidance given to his wife, he orders weekly production. The required funds do come in, enough to pay the bills.

And so the workers press on, a day at a time, week by week, month by month. Their compensation? A place to sleep, and simple food to eat. But morale is good. Like Isaiah they are publishing the good news: “Thy God reigneth.”

Taking to the Road

Operations are complicated when the Whites embark on preaching tours so vital to the struggling movement. In the spring they go westward, conducting Sabbath conferences in several states. In the autumn, after farmers have harvested their crops, they travel east and north into New England and Canada. Their rickety carriage is drawn by Charlie, their aging but faithful horse.

Their average was 23 — not counting the children!

Roads are unpaved; long sections consist of logs laid crosswise, imposing constant jolts to passengers. They frequently bump through miles of deep woods, where the darkened roadways seem like endless tunnels. There are no highways, no freeways, in the territory they traverse. Only a network of farm roads threads through the countryside. As they pass by orchards, Charlie pauses to enjoy a ripe apple that hangs over the road.

Sore from the constant jarring, they stop for lunch where there is grass for the old horse. James writes for the Review or Youth’s Instructor, his top hat or lunch box serving as desk. Ellen comforts a baby, often sick, who rests only while in her arms. There are no conveniences, but they are happy. They have a vision. They are driven by a dream.

James has published their travel itinerary in the Review. They expect and usually find companies of Adventist believers waiting for them. After several days of preaching, exhortation, and reproof in each locale, they drive to the next town on the published schedule. Two months and 2,000 miles later, old Charlie draws them back to Rochester and home. Members of the publishing staff, eager for news of the trip, greet them with joy.

While away, James and Ellen have sent editorials and articles by mail for publication. Annie Smith has coordinated the editorial production in their absence, literally keeping the operation alive. Her contributions have been critical. But each member of the Review family is vital to the success of this volunteer, self-supporting venture.

More on Annie Smith

James White, the editor of the Review and Herald, impressed with Annie’s poem and doubtless familiar with her talents through her mother, immediately wrote asking her to come to Saratoga Springs, New York, to assist him as a copy editor. She hesitated, pleading her eye trouble as a reason she could not accept. He told her to come anyway, and upon her arrival, she was quickly healed after anointing and prayer. Ellen White took note of Annie’s coming in a letter to a friend: “Annie Smith is with us. She is just the help we need, and takes right hold with James and helps him much. We can leave her now to get off the papers and can go out more among the flock.”

Meet the Team

Imagine James White, editor and publisher, introducing the team around him. He says, “Well, you know me. I am 32, and my wife, Ellen, is 26. Here are our children, Henry, 6, and Edson, 4. Standing there with them is Clarissa Bonfoey. She has taken faithful care of Edson. She is 32. Next to her is Annie Smith, age 25. She fills my place when I am away and is indispensable all the time. Her brother, Uriah, 21, is a budding author who helps with any kind of work that needs to be done.

“Then we have several young folks who are learning the printing business from Mr. Masten. George Amadon is 21, and Oswald Stowell is 25. Fletcher Byington is 20 and Warren Bacheller is 14.

“Jennie Frazier is our cook. We sample her product three times a day. Next Luman Masten, our printer, who is 24.

“Here are two hardworking folks who came with us from Saratoga Springs, Stephen and Sarah Belden, age 24 and 20, respectively. Stephen helps me with the business angle of the work, while Sarah, Ellen’s sister, takes care of the household, with its continual round of cleaning, mending, washing, and sewing.

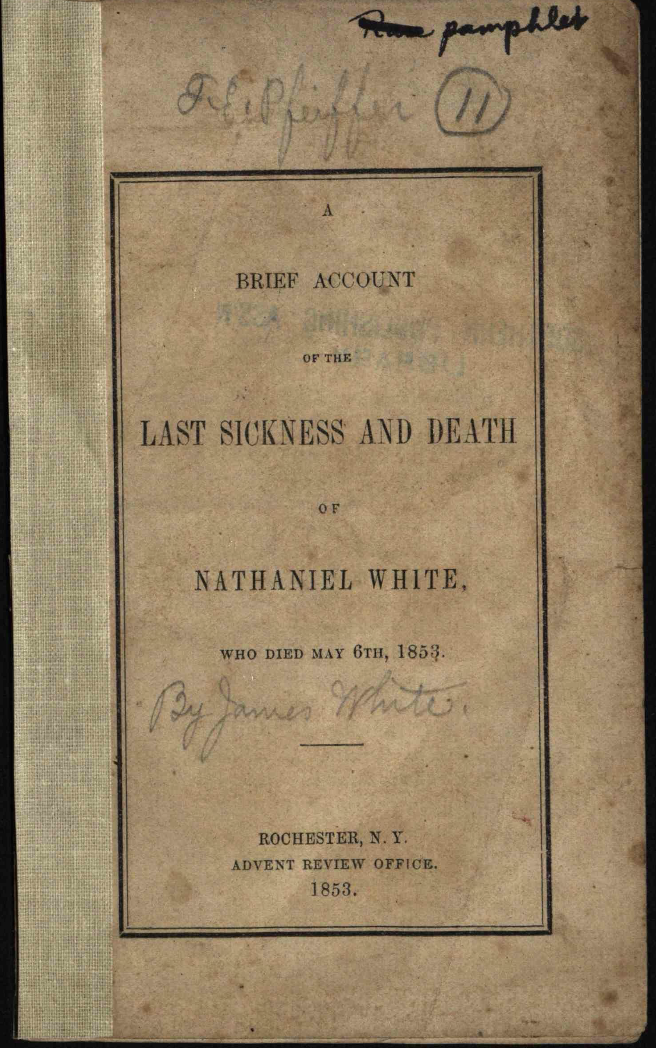

“Finally, we have two new additions. These are Nathaniel and Anna White, my brother and sister. Nathaniel is 22, and Anna, 25. . . .

“John Loughborough and his wife live here in Rochester. When he isn’t out preaching, he comes around and gives us a hand in the pressroom. He is 21.

By today’s management standards, they were marked for chaos and failure.

John Andrews, one of our competent writers, also drops by at times for a rest. But most of the time he’s in the field preaching also. He is 24… Only three of us are over 30. Our average age is 23, and that isn’t counting the children!

But the hardworking young Review and Herald team of which James is so proud will be sorely tested. Annie Smith grows gravely ill with tuberculosis, and soon dies. Nathaniel, James’s brother, and Anna, his sister, also succumb to the deadly disease as James himself battles its symptoms. Anna White and Annie Smith have been linchpins of the operation: Anna has been editing the Youth’s Instructor; Annie has kept the weekly Review coming off the press. Their loss and that of Nathaniel White threaten to cripple the publishing effort.

If the work is going to continue to grow, someone must be found to serve as editorial assistant to James White. Uriah, Annie’s young brother, is selected. Like his sister, Uriah is a gifted writer and poet; unlike Annie, whose hymns continue to be sung by modern Seventh-day Adventists, Uriah’s poetry is rarely set to music: one poem is 35,000 words in length! Convinced of the doctrinal if not the musical value of the piece, James White orders that it be printed in successive weekly editions of the Review.

Modern historians of the Adventist movement assert that the young volunteers who labored so creatively and tirelessly at Rochester for three years are largely responsible for the coalescing of believers who later organized the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Though probably unaware of the full impact of their labors, they worked with rare diligence and at great personal sacrifice. Their effort is singularly responsible for maintaining widespread and focused interest in Christ’s second coming as well as introducing the distinctive Bible truths now familiar to Adventists.

Limited by primitive, inadequate equipment and facilities, the Rochester company gave stability and form to the publishing work, which, in turn, supported the preaching of the Adventist message by the Whites, Joseph Bates, John Loughborough, John Andrews, and others. This company of humble, hardworking young adults brought unity and strength to what had been a fragmented and scattered movement. Often bone-tired and in need of sleep, they maintained demanding production schedules. “The message,” they insisted, “must go forward!”

Untrained but Undeterred

From a human standpoint, neither James nor Ellen White was qualified for the extraordinary role they played. Nevertheless, James, with approximately 10 months’ formal education, was a respected leader, a gifted and popular preacher, as well as an effective writer and editor. Ellen had not completed the third grade, and was at best a frail young woman, yet she wrote prodigiously, and when speaking, even in the open and without amplification, held the attention of hundreds and even thousands of listeners. Both suffered from ill health and were burdened with family needs and problems. They pressed forward without sponsorship as self-supporting workers.

Why did they and their colleagues do it? How did the little group at Rochester accomplish so much? What moved them to work harmoniously 10, 12, even 18 hours a day as self-supporting volunteers under conditions that most Adventists, then and now, would deem unacceptable?

Though probably unaware of the full impact of their labors, they worked with rare diligence and at great personal sacrifice. Their effort is singularly responsible for maintaining widespread and focused interest in Christ’s second coming as well as introducing the distinctive Bible truths now familiar to Adventists.

They came from different faith backgrounds, different ways of reading Scripture, different environments. They were young, poor, and for the most part not formally educated. Several were terminally ill.

They were not linked to any church organization, nor did they enjoy warm relationships with existing denominations. They had no church or corporate name. By today’s management standards, they were marked for chaos and failure. But they joined together in an enterprise to tell to the world the cosmic concepts and convictions that had excited their thinking and warmed their hearts. Inspired by a divine vision, they found an insistent energy in the dream that the words they wrote and set in type would go like streams of light around the world. Like Abraham, they had no abiding city here, for they looked “for a city which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God.”

Today the Review they labored over is read by hundreds of thousands around the world. Printed in five major world languages, its articles are translated into dozens of additional dialects and reprinted around the globe. The magazines and tracts they initiated have won tens of thousands to faith in the second coming of Jesus and the beauty of the Sabbath truth. The publishing effort they launched with muscle power, calluses, and tears now produces millions of pieces of gospel literature each year. The dream of truth going “like streams of light . . . clear round the world” has been realized on a scale that most of them could scarcely have imagined.

Like the psalmist, they found their deepest and most lasting significance in the hastening of that kingdom they sought with all their passion. Driven by a dream of bringing glory to Jesus, their sweat and their suffering and their tears became their abiding prayer: “Not unto us, O Lord, not unto us, but unto thy name give glory.”

(The original article was published as a cover story for the Adventist Review online edition. It has since been archived and can be found here. It was written by Oliver Jacques, a retired pastor and teacher, and a great-grandson of James and Ellen White)