Let none this humble work assail,

Its failings to expose to view,

Which sprung within Misfortune’s vale

And ‘neath the dews of Sorrow grew.

Thus does Annie Rebekah Smith, the early Adventist hymnist, beg indulgent tolerance of the little book of poems she completed on her deathbed in 1855. Her wishes will be honored here in favor of a modest effort to tell the simple story of her short, sad life.

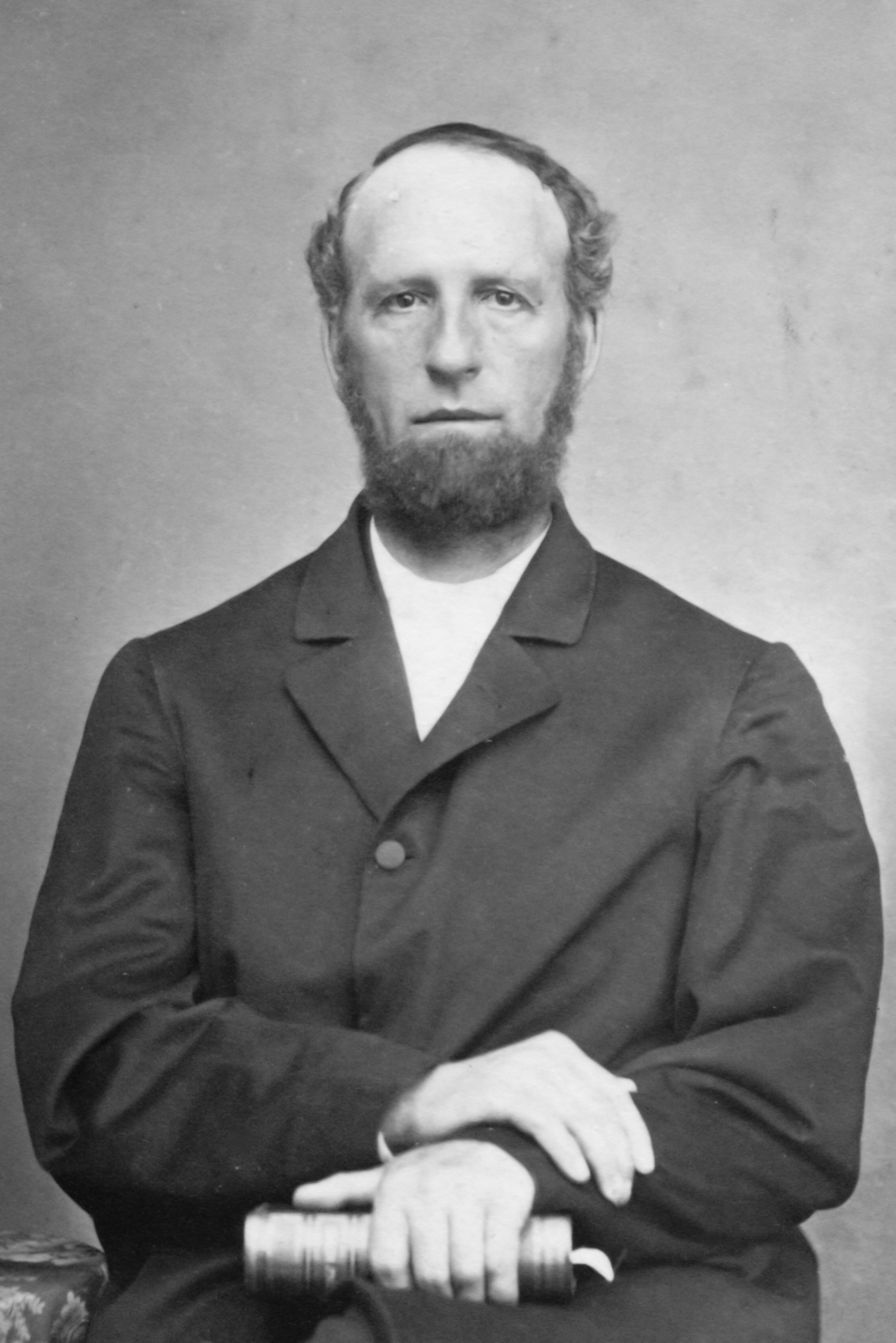

Most of what is known about her comes from a little sketch of her life included in another book of poems published by her mother, Rebekah Smith, in 1871. From this we learn that Annie was born in West Wilton, New Hampshire, on March 16, 1828, the only daughter of Samuel and Rebekah Smith. She was four years older than her better-known brother, Uriah, and four months younger than the best-known of Adventist women, Ellen G. White.

At 10, Annie was converted and joined the Baptist Church. With her mother, she left that communion in 1844 to throw her youthful energies into preparation for the second advent of Christ.

When the clouds of October 22, 1844, turned out to be only those that draped another drab New England day instead of a host of angels, Annie turned her attention to study and teaching. For the next six years she alternated between teaching in seven different district schools and pursuing her own intellectual enrichment.

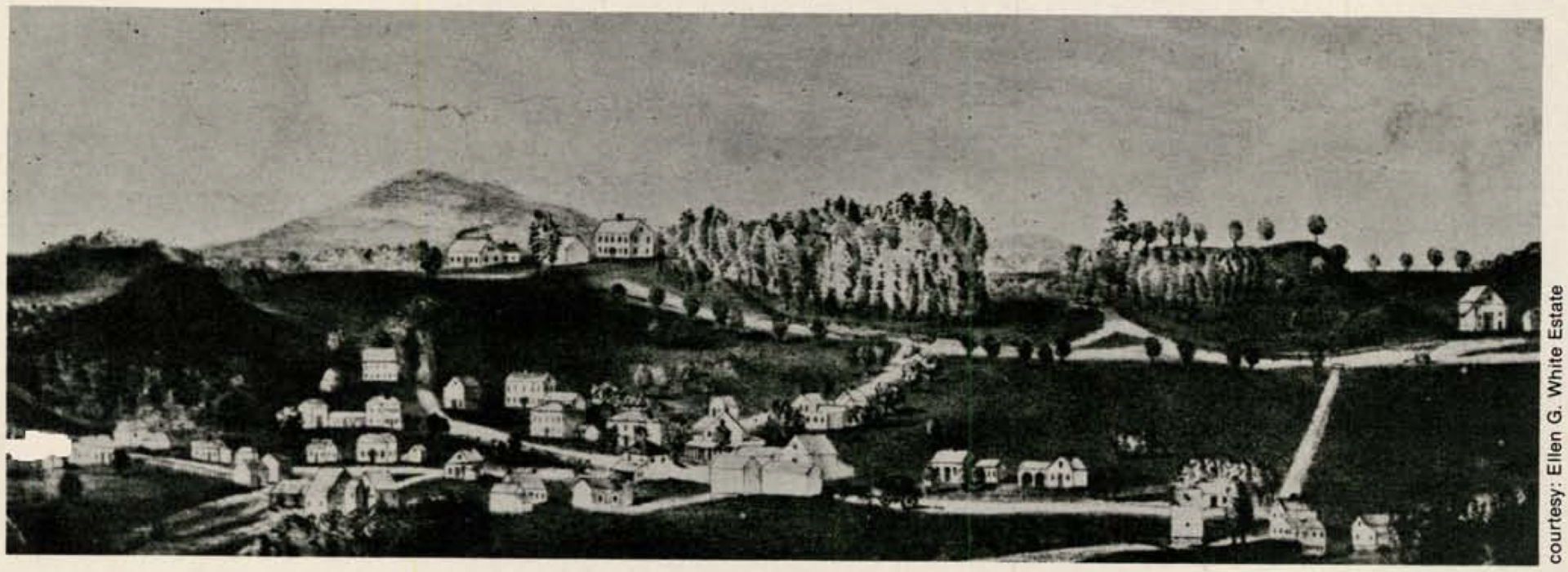

She spent six terms at the Charlestown Female Seminary in Charlestown, Massachusetts, next door to Boston. The seminary, chartered in 1833, offered courses in English, philosophy, Romance languages, Latin, Hebrew, music, and art. There were also free lectures in anatomy, physiology, and chemistry.

The school year was divided into three terms — a twelve-week fall session and winter and spring terms of sixteen and seventeen weeks. Most likely Annie taught in the grammar schools near her home during then winter and then, while the youngsters went to work on the farms, she would go to Charlestown in mid-April to attend the spring term at the Seminary.

Although her mother only mentions that she studied French and Oil Painting, it seems probable that she might have delved into other subjects as well during the course of her six terms at the school. She was not, however, a regular student, and was not listed with the other students in any of the school’s catalogues during the years she attended.

The seminary was ostensibly nondenominational but it was far from irreligious. There were regular weekly Bible lessons, and each young lady was expected to come equipped with her own Bible, whatever commentary she may have had, plus other books “containing moral and religious instruction, suitable for Sabbath reading.” The students were required to attend church twice each Sunday at some stated place. Just where Annie may have chosen to attend is unknown, but if, after her Millerite adventure, she reverted to her former denominational affiliation, she would have found things in Charlestown nicely arranged: her school was located on the corner of Union and Lawrence Streets with the First Baptist Church at the other end of the block.

During what what was probably her first term at the Seminary in 1845, the Reverend Edward Beecher, pastor of Boston’s Salem Church, addressed the students and faculty in a lecture titled “Faith Essential to a Complete Education.” The philosophy was pervasive not only at the Charlestown Female Seminary, but throughout the American public school system of the time.

During Annie’s last term at the seminary, in 1850, she was definitely enrolled in an art course. One day, while sketching a a picture of Boston from Prospect Hill in Somerville, she strained her eyes and for eight months could hardly use them. This brought her to another disappointment in life. She was unable to accept a coveted position in a school at Hancock, New Hampshire.

To alleviate her unhappiness, she became an agent and, according to her mother, a frequent contributor to The Ladies’ Wreath, an elegant literary magazine published in New York. Four poems from her pen appeared in this publication within two years. She is also said to have contributed a few pieces to The Odd Fellow, but so far her contributions to the paper have not been located.

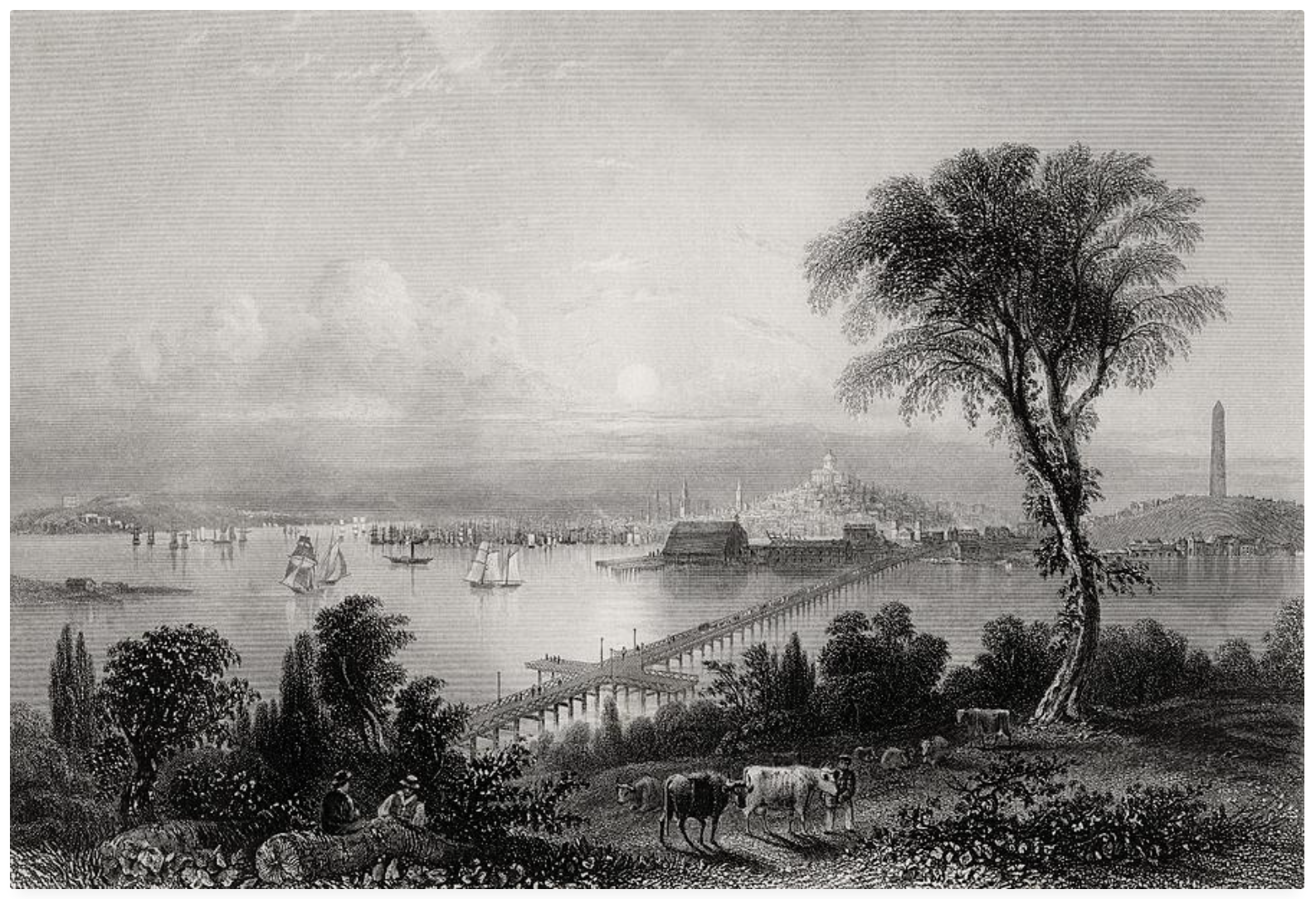

Thinking the salt-air of Charlestown would be good for her eyes, Annie remained there with friends. She must not have been too blind, because during her stay she ventured north to Portland, Maine, and on to Nova Scotia.

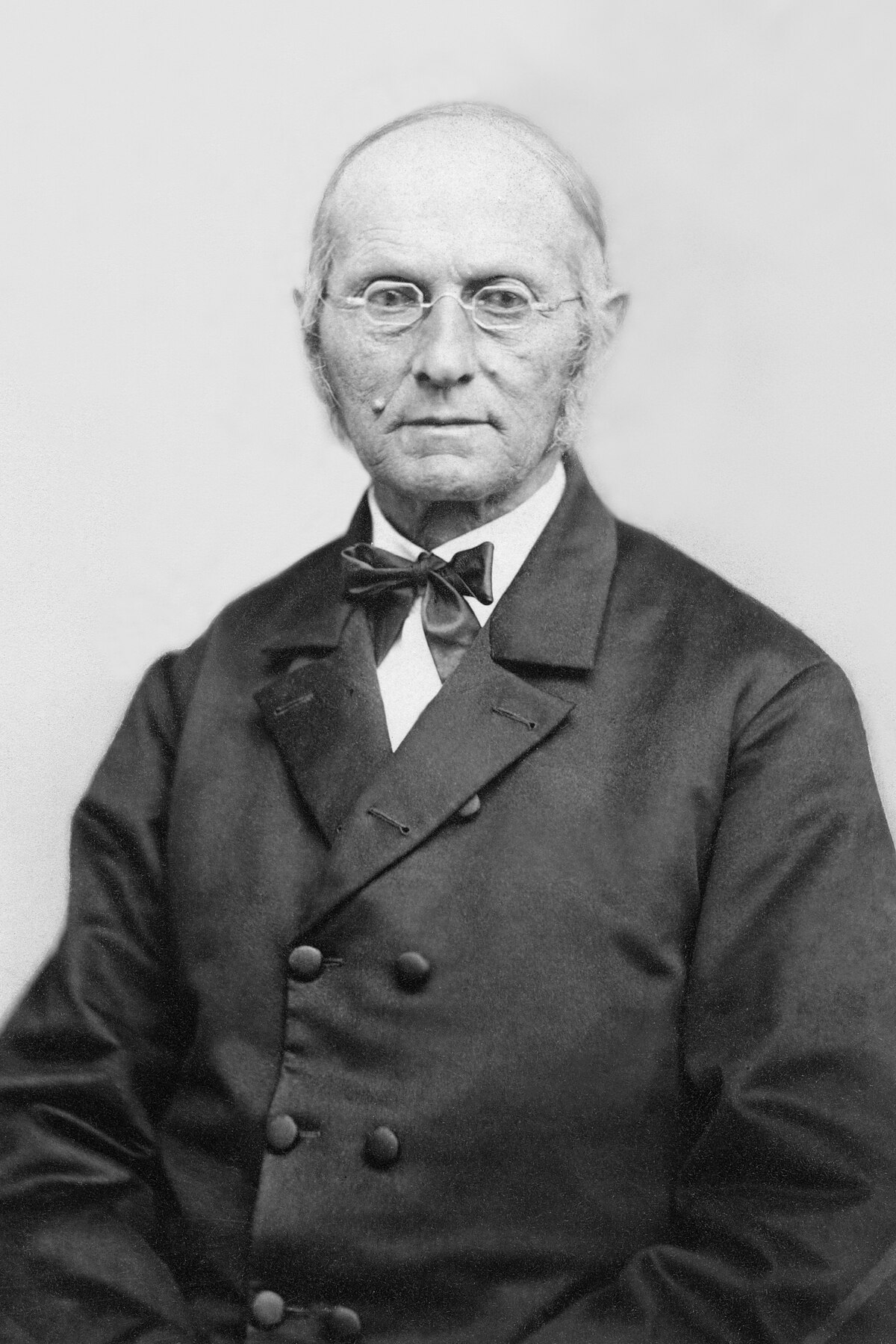

Meanwhile, her mother was becoming more and more concerned about Annie’s avid pursuit of secular success in literature and art. When Joseph Bates, the sea captain who became an Adventist preacher, visited the Smith home in West Wilton, Mrs. Smith shared her burden with him. Since he was to be in Boston in a few days, he urged the mother to write Annie inviting her to his meetings. Contrary to J.N. Loughborough’s account, the services were to be held at Elizabeth Temple’s home in Boston, not at the Folsom residence in Somerville.

The night before the first meeting Bates had a dream. In it every seat in the room was filled except one next to the door. The first hymn was sung, and then, just as he opened his Bible to preach, the door opened and a young lady entered, taking the last vacant chair.

The same night Annie had virtually the same dream. The next evening she set out for the meeting in ample time, but lost her way. She entered just at the moment the dream had specified. Bates had been planning to talk on another subject, but remembering his dream, he switched to a sermon on the Adventist view of the Hebrew sanctuary.

At the close of the meeting he stepped up to Annie and said: “I believe this is Sister Smith’s daughter, of West Wilton. I never saw you before, but your countenance looks familiar. I dreamed of seeing you last night.” Annie related her own dream and was deeply impressed with the turn of events.

Joseph Bates, in his letter to the Review and Herald reporting this visit to Boston, merely says: “We spent the Sabbath and first-day July 2 and 27, in meeting with about twenty believers, at No. 67 Warren Place, where the meetings are to be held every Sabbath…Here two, that had formerly believed the advent doctrine, embraced the last message.”

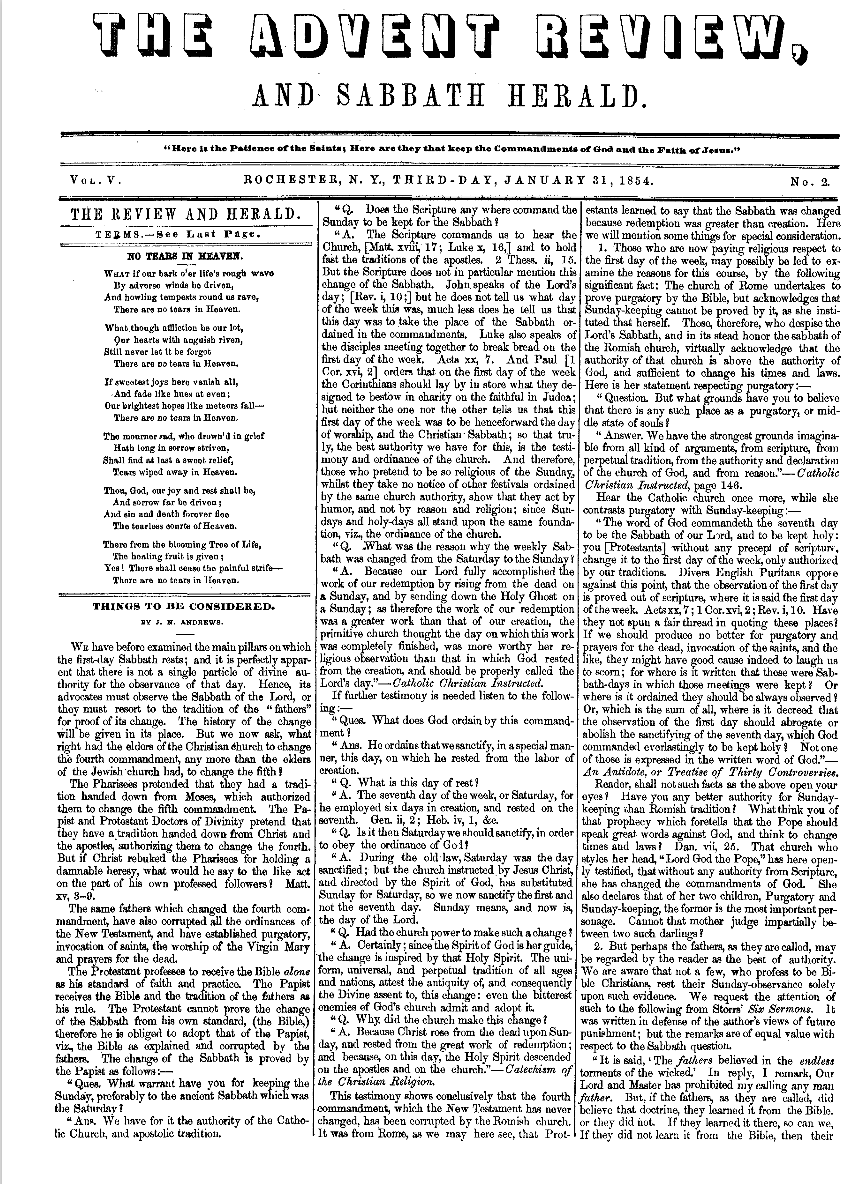

A month after she attended Bates’s meetings, Annie sent a poem, “Fear Not, Little Flock,” to the Review, along with a letter: “It is with much reluctance that I send you these verses, on a subject which a few weeks since was so foreign to my thoughts. Being as it were a child in this glorious cause, I feel unworthy and unable to approach a subject of such moment, but as I’ve written for the world, and wish to make a full sacrifice, I am introduced to send.”

Both the letter and the poem appeared in the Review, and the latter indicated Annie’s interest in hymns. The last stanza read:

Hallelujah’s we’ll raise,

Our Redeemer to praise

With the pure and the blest,

In the Eden of Love be forever at Rest.

The phrase, “Eden of Love,” used in the last line of the poem is the title of an infectiously beautiful folk-hymn that was carried over from the Millerite movement into Adventist hymnody.

James White, the editor of the Review and Herald, impressed with Annie’s poem and doubtless familiar with her talents through her mother, immediately wrote asking her to come to Saratoga Springs, New York, to assist him as a copy editor. She hesitated, pleading her eye trouble as a reason she could not accept. He told her to come anyway, and upon her arrival, she was quickly healed after anointing and prayer. Ellen White took note of Annie’s coming in a letter to a friend: “Annie Smith is with us. She is just the help we need, and takes right hold with James and helps him much. We can leave her now to get off the papers and can go out more among the flock.”

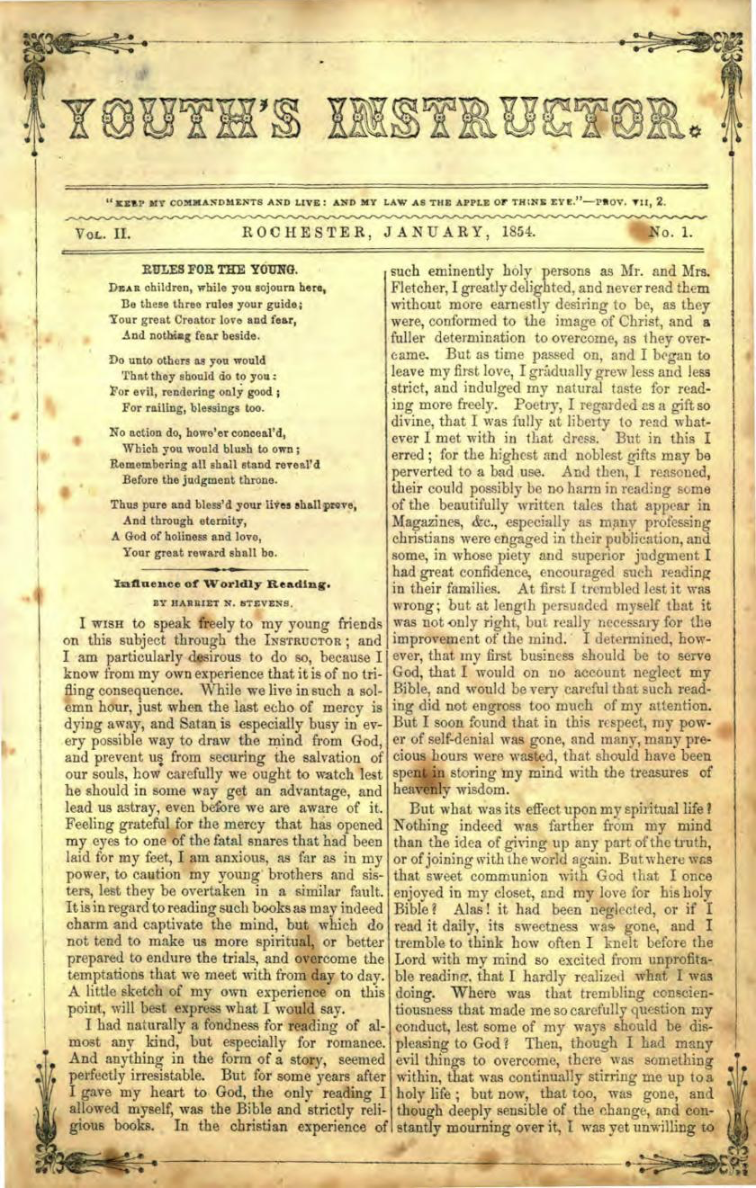

Although most of Annie’s time was spent in the drudgery of copy editing, she was occasionally given full responsibility for the Review while the Whites were away on preaching tours. She continued to write hymns and poetry as well, contributing a total of 45 pieces to the Review and the Youth’s Instructor before her death three and a half years later. Ten of her hymns survive in the current Seventh-day Adventist Church Hymnal.

Learn the hymn

Printables, piano accompaniment, hymn text and other tidbits are all available in this site.

Annie had lived with the Whites in Saratoga Springs for only a few months when they moved to Rochester. Shortly before the move she turned 24. Times were hard for the little group of workers in Rochester. Ellen White tells how they had to use turnips for potatoes. Annie’s work was not always easy, either. James White, driving hard in these difficult early days, could be a demanding taskmaster. Most of Annie’s poetry was deeply and seriously religious, but she did venture one lighthearted rhyme that may reflect something of James White’s eagerness that the Review be a perfect paper. The poem was titled “The Proof-Reader’s Lament”:

What news is this falls on my ear?

What next will to my sight appear?

My brain doth whirl, my heart doth quake —

Oh, that egregious mistake!

“Too bad! too bad!!” I hear them cry,

“You might have seen with half an eye!

Strange! passing strange!! how could you make

So plain, so blunderous a mistake!”

Guilty, condemned, I trembling stand,

With pressing cares on every hand,

Without one single plea to make,

For leaving such a bad mistake.

If right, no meed of praise is won,

No more duty then is done;

If wrong, then censure I partake,

Deserving such a gross mistake.

How long shall I o’er this bewail?

“The best,” ‘tis said, “will sometimes fail;”

Must it then peace forever break—

Summed up, ‘tis only a mistake.

In spite of whatever difficulties may have arisen, the Whites must have appreciated Annie and her work. James sent her a gift of $75 during her last illness, and Annie’s mother, writing of the bond of affection between her daughter and the Whites, said, “Annie loved them.”

(To be continued)