There was someone else whom Annie loved: the handsome young preacher, John Nevins Andrews. John lived in Rochester during the time Annie was there. They were about the same age, and both were bright and intellectually ambitious. There are indications that Annie had high hopes for her future with John, but he disappointed her, turning his affections to Angeline Steven, a girl from his hometown of Paris, Maine.

The evidence for Annie’s love and subsequent heartbreak lies half-buried in a letter Ellen White wrote to John just one month after Annie’s death: “I saw that you could do no better than to marry Angeline; that after you had gone thus far it would be wronging Angeline to have it stop here. The best course you can now take is to move on, get married, and do what you can in the cause of God. Annie’s disappointment cost her her life.”

Ellen White appears to be saying: Don’t do the same thing to Angeline that you did to Annie. Now that you’ve raised her expectations, go ahead and marry her. Judgments based on a single piece of evidence may seem a bit hazardous, but when Ellen White’s comments are linked with certain passages in Annie’s own poetry, it is more certain that Annie was jilted by John.

In the spring of 1854 she wrote two religious poems which may reflect something of this experience:

If other’s joys [Angeline’s?] seem more than thine,

Pause, ere thou at this repine;

Life hath full enough of woe,

For the sunniest path below.

And in a poem titled “Resignation” she wrote:

Thou art the refuge of my soul,

My hope when earthly comforts flee,

My strength while life’s rough billows roll,

My joy through all eternity.

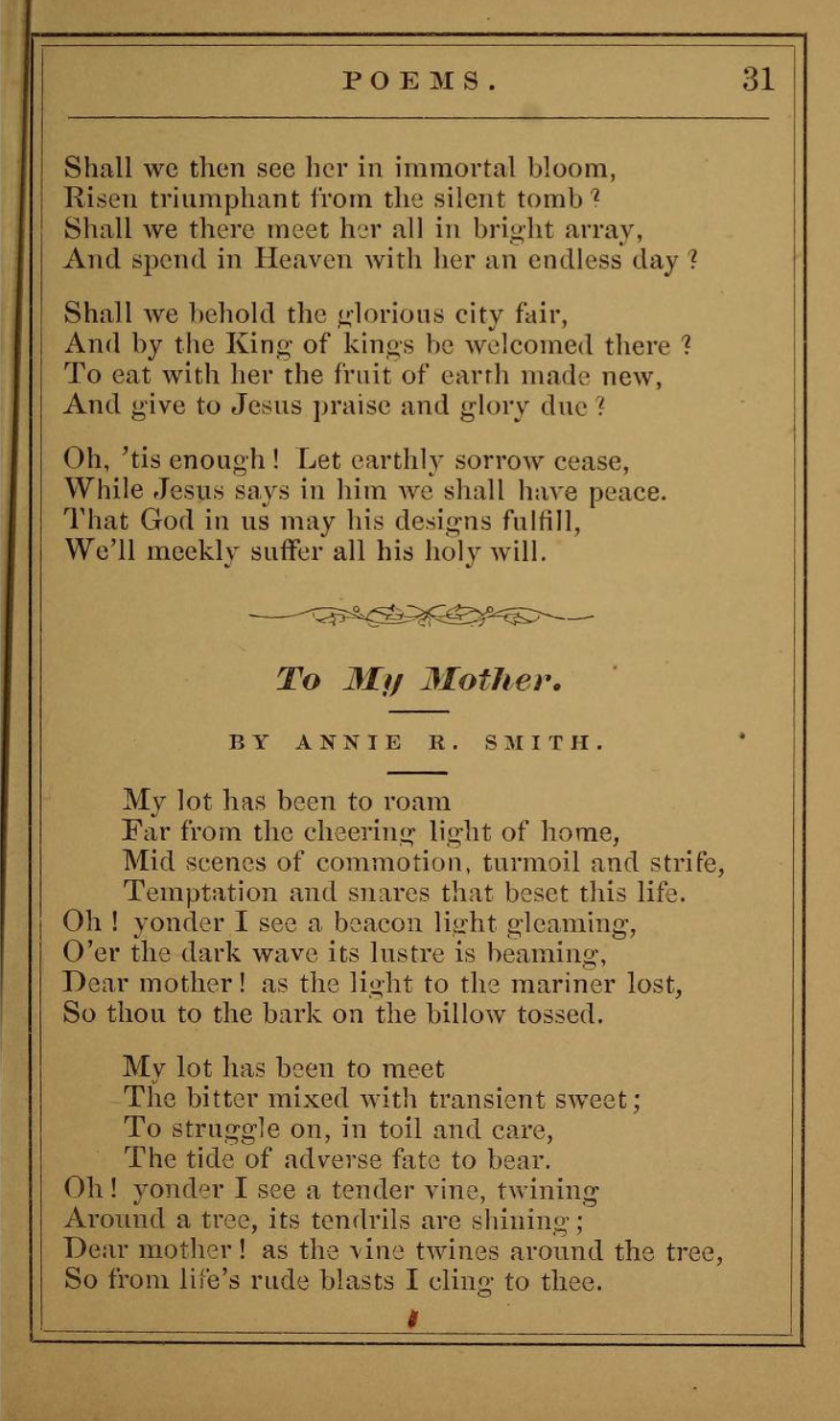

But Annie’s most personal feelings on this subject would hardly be found in her religious poetry, printed as it was in the Review for J.N. Andrews and everyone else to read. Her mother’s book, published in 1871, includes a good selection of Annie’s secular verse. One of these was a poem addressed to her mother:

My lot has been been to learn

Of friendship false, that bright will burn

When fortune spreads her wing of light,

But fades away when cometh night.

“Dear Annie,” her mother wrote in her “Response”:

What though thy lot has been to bear

Much adverse fate, ‘mid toil and care

Raised expectations crushed and dead

And hope’s triumphant visions fled?

***

Does not thy heart begin to feel

The claims of Him who wounds to heal?

Were it not that Mrs. Smith’s “Response” specifies that Annie’s crushed expectations came “mid toil and care,” the mention of “friendship false” in Annie’s own poem might have referred to some disappointments she suffered during her school days in Charlestown. Of the four poems she wrote for The Ladies’ Wreath during the time just before she became an Adventist, two speak of blighted love. If nothing less, these secular poems indicate something which her sober hymns do not: that she was capable of feeling the whole range of emotions connected with youthful love. In “Trust Not — Love Not,” she wrote:

Love’s sweet strain, like music flowing,

Drink not deep its melting tone:

Eyes that now so gently glowing,

Beaming fondly in thine own —

Lips will smile, but too deceive thee,

Tender glances, heed them not:

For their coldness soon may grieve thee,

Soon thou mayest be forgot.

Witness also these lines from a ballad-like poem, “The Unchanged”:

The morn of youth was on her cheek when lover her bosom thrilled,

With golden dreams of future bliss her gentle soul was filled—

His dark eyes woke the flame within of soul lit, lustrous hue,

To be unquenched — the holy light of pure devotion true.

And oft she gazed with rapture on that bright angelic face,

So radiant and beautiful with eloquence and grace:

His voice, like tones of music sweet, bound with a magic spell,

As gems of wisdom from his lips in heavenly accents fell.

I saw her in the moonlit vale, a lovely maiden’s form,

Her spirit in illusions wrapped, her cheek with vigor warm;

Untouched by sorrow’s withering hand, so pale, for hers were dreams

Of other years — that for the night had cast their halo beams.

The possibility that Annie may have been in love with J.N. Andrews adds a new dimension to the controversy over her hymn “I Saw One Weary, Sad, and Torn” (Hymns and Tunes, No. 667). Each verse of the hymn has been thought to be an ode to one of the Adventist pioneers contemporary to her. The first two stanzas are assigned respectively to Jospeh Bates and James White. Bates is identified by the “many a line of grief and care,” which on his brow were “furrowed there.” He was much older than any of the other pioneers. James White is almost certainly the one who “boldly brave the world’s cold frown” and was “worn by toil, oppressed by foes.” But who was the Adventist who

…left behind

The cherished friends of early years,

And honor, pleasure, wealth resigned,

To tread the path bedewed with tears.

Through trials deep and conflicts sore,

Yet still a smile of joy her wore:

I asked what buoyed his spirits up,

“O this!” said he — “the blessed hope.”

Learn the hymn

Printables, piano accompaniment, hymn text and other tidbits are all available in this site.

Three possible candidates have been suggested for this stanza: Uriah Smith, Andrews, and Annie Smith herself disguised in masculine pronouns. Uriah is eliminated on chronological grounds. He had not yet accepted the “third angel’s message” at the time Annie wrote the hymn. The hymn was published August 19, 1852, about a year after Annie’s conversion, five months after her her arrival in Rochester, and just enough time for a friendship with John to blossom.

But Annie herself cannot be ruled out as a candidate. She certainly felt that she had renounced “honor, pleasure, and wealth” to become an Adventist. In the same poem in which she makes the allusion to “friendship false,” she says:

My lot has been to pore

Learning’s classic pages o’er:

Seeking for hidden pearls to wear,

Fame’s golden wreath, the victors bear.

She had been on the brink of fame, or at least thought so, and for her to turn her back on it was a special trial. Naturally, if she was writing about herself in the hymn, she could not reveal it, but all the details of the third stanza fits Annie perfectly. The problem is that they also fit John. The question of whether the stanza refers to John or Annie, may never be solved, and perhaps it is fitting that they are linked in this mystery.

It is no wonder that many of Annie’s hymns were so somber. Not only was she an Adventist in a day when Adventists were scorned and despised, not only did she give up her hope of worldly fame, not only was she thwarted in love, but death itself was stalking her. She had been with the Review for barely a year when she was called home for the death of her father, Samuel Smith. When she returned to the office in Rochester late in December, 1852, she found that James White’s brother Nathaniel and his sister Anna had arrived, both suffering from tuberculosis.

Anna White soon took over the editorship of the newly launched Youth’s Instructor to which Annie contributed an occasional poem. But Nathaniel lived only till May of 1853. Annie commemorated his death with a poem. About a year later Luman V. Masten, another of the young workers in the office, died of tuberculosis. Again Annie wrote a poem, a portion of which read:

Then mourn not the loss of our dear, absent brother

Bright angels shall watch o’er the dust where he’s laid

To rest by the side of his fondly-loved mother,

Who for his salvation so fervently prayed.

Annie Contracts Disease

In November of that same year, 1854, Annie returned to her home in West Wilton, suffering from the first stages of tuberculosis herself. She had just arrived when word came that Anna White had died of the disease. The poem she wrote for Anna became a hymn which would be sung at her own funeral:

She hath passed Death’s chilling billow,

And gone to rest:

Jesus smoothed her dying pillow—

Her slumbers blest.

Annie arrived home November 7. A month later she was coughing blood. Her mother says that since she had “confidence in water treatment, she went where she could receive such.” Perhaps she traveled to nearby New Ipswich where, according to the Water-Cure Journal of June, 1853, a Mr. Amos Hatch operated a hydropathic institution.

But the treatment did not help, and Annie returned home in February, just in time for a visit from Joseph Bates. “At the commencement of the Sabbath, the 16th,” her mother wrote, “the spirit and power of God descended upon her, and she praised God with a loud voice…Bro. B. then said to Annie, ‘You needed this blessing, and now if the Lord sees that it is best for you to be laid away in the grave, He will go with you.’ “

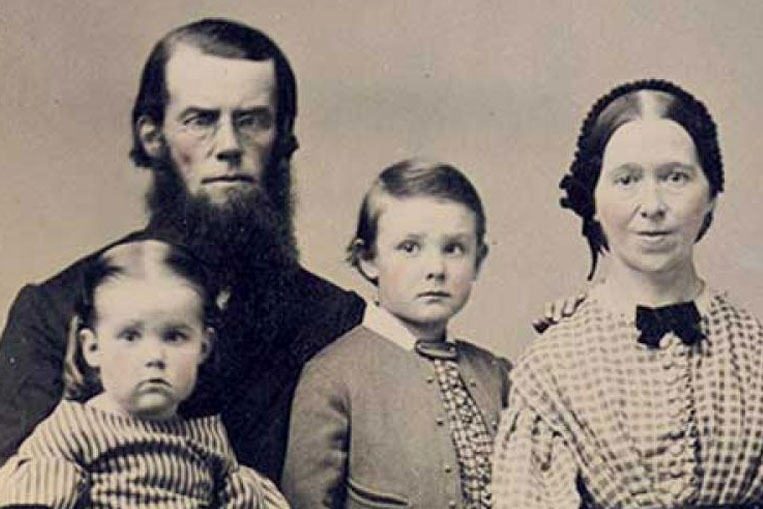

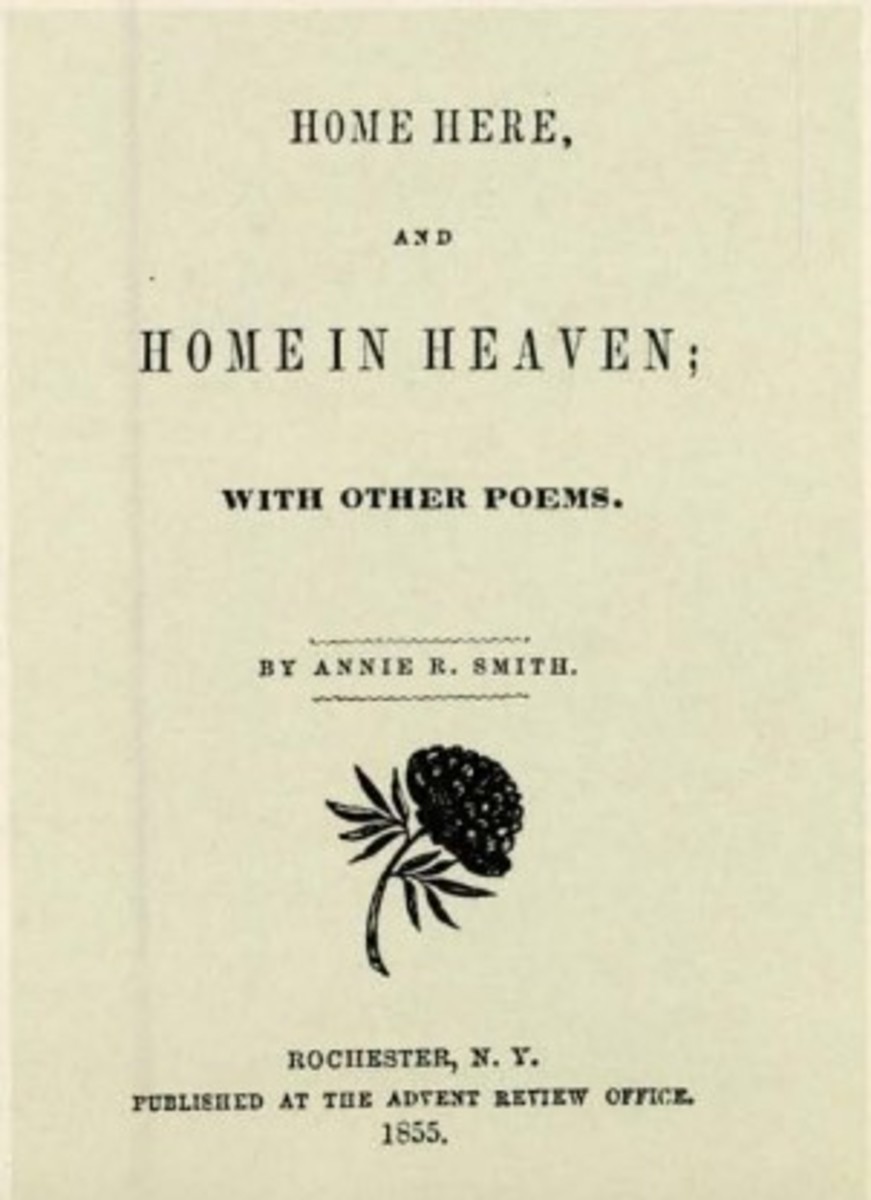

But Annie prayed for just one more privilege before she died. She wanted to be able to finish her long poem, “Home Here and Home in Heaven,” and publish the little book of poetry she had been planning. Her brother Uriah came home in May, and helped her to copy and arrange her poetry for publication. As soon as the flowers blossomed that spring, he sketched and engraved a peony, her favorite, to go on the title page of her book.

Annie told her mother that she believed there would be a change in her condition once the book was completed. Either she would be healed or she would die. She lived less than ten days after she finished her work.

Her mother chronicled the last days of her 27-year-old daughter in great detail. On the eighteenth of July Annie wrote a poem titled “Our Duty”:

Never from the future borrow

Burdens that no good repay,

Strength required for to-morrow,

May be lost on us today.

At three o’clock the next afternoon she said: Mother, some change has taken place. I don’t think I shall live through the day.” “I saw there was a change,” her mother wrote, “and stayed by her. Night drew on. No one happened in. She said, ‘It seems to me I could not breathe to have many in the room..’ “ Her mother told her her she was not afraid to be alone with her if she died. Through the night the mother and her semi-invalid brother John watched. It seemed that each moment must be her last.

About two in the morning she rallied some, and looked very happy. “Annie is being blessed,” Mrs. Smith said to John. Soon Annie exclaimed, “Glory to God” a number of times, louder than she had spoken for a long while. “Heaven is opened,” she said. I shall come forth at the first resurrection.”

Uriah had returned to Rochester by now, hoping he could get the type for Annie’s book and let her see the proof sheets before she died. Mrs. Smith wanted to write him and urge him to come home at once, but Annie said: “It will make no difference, I think I am dying; don’t leave me, Mother, while I live.”

The fact that Mrs. Smith would write a vivid day by day account of Annie’s decline reflects the Victorian tendency to romanticize illness and death. Ninteenth-century Americans, Adventists included, were far less inclined to disguise or avoid death than we are today. Annie and her mother talked freely about her death long before it occurred. Her mother did not not look back on those last days as some hideous shame to be expunged from memory, but as something worth preserving in every detail.

On Tuesday morning, July 24, Annie composed her last poem:

Oh! shed not a tear o’er the spot where I sleep;

For the living and not for the dead ye may weep;

Why mourn for the weary who sweetly repose,

Free in the grave from life’s burden and woes?

No recasting can improve the poignant forcefulness of her mother’s account of her last hours:

Tuesday night was a solemn and interesting night. I stayed with her alone through the night. Neither of us slept. She was very happy, and talked much with me. She said in her former familiar way, “My mother, I’ve been afraid I should wear you all out. I’ve called after you by night and by day.” She felt bad to have have kept up as I was on her account. But she said, “I am here now, your dying girl. I think this is the last night, and you must be sure to rest when I am gone. O, my blessed mother, I shall bless you in Heaven for taking such care of me. No sorrow or suffering there. We shall all be free there. Yes, we shall all be free when we arrive at home, and we shall live forever. Yes, and I can smile upon you now through all my sufferings.” It was her last sufferning night. Wednesday, the 25th, a death coldness was upon her. In the afternoon she beccame more free from pain and distress. While speaking in the evening of taking care of her, she said, I shall not want any one to sit up; you can lie on the lounge.” At 1 o’clock I called Samuel [another brother]. She talked with him, called for what she wanted as usual, and told him he might lie down. About three o’clock she called him to wet her head with water, and said she felt sleepy. She was indeed going into her last sleep. Samuel wet her head, and soon after spoke to me and said, “I don’t know but Annie is dying.” I spoke to her. She took no notice, breathed a few times, and died apparently as easy as anyone going into a natural sleep. Her sufferings were over. She was gone. It was 4 o’clock in the morning, July 26, 1855.

Of Annie it can be said that in her affliction “still a smile of joy” she wore. What sustained her? What buoyed her spirits up? “O this,” she replies, “the blessed hope.”

(This article is written by Ron Graybill, who at that time this was written was a research assistant at the Ellen G. White Estate and a graduate student in American religious history at John Hopkins University. He later became at the Executive Secretary of the said estate but had to be reassigned to another post years later. This article is adapted from the Adventist Heritage, A Magazine of Adventist History, Summer, 1975, Volume 2, Number 1 . An edited version can be found in the Review, with several paragraphs removed. We have included the last paragraph from the Review’s version in this post.)